The Sentiment

3And then there was no more Empire all of a sudden.

—Derek Walcott

Its victories were air, its dominions dirt . . .

Days into the US intervention in Haiti in September 1994, the New York Times featured a photo of a coconut vendor lying dead on a Port-au-Prince street, face beaten and body bruised. The headline, “Haitian Police Crush Rally as American Troops Watch,” was possibly a critique of US foreign policy at this volatile moment in Haiti’s political history, but it’s difficult to tell.1 The image appears to function as both illustration and indictment, making visual the mortal trajectory of both the vendor and the photograph, reinforcing the that has been that Roland Barthes reminds us exists in each photographic image.2 In the image of the deceased vendor, we have no view of American soldiers, no photo of any of the 3,300 troops deployed to the region under orders to observe but not interfere. It is fitting, then, that the concluding chapter of Mortevivum begins in Haiti, where sentiment ends.

Cover page of the New York Times, September 21, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International. This image has been altered from its original form.

The article accompanying the photograph did much to consider the feelings of the American soldiers, men and women who, having newly arrived and eager to be of some use, were feeling “helpless,” “frustrated,” and “disgusted” at their inability to step in and control the escalating violence amid President Aristide’s exile and attempted overthrow. About the nameless Haitian man sprawled on the cover of the international newspaper, though, there is no such consideration. Times writer John Kifner wrote of the vendor, “He was a thin man, his arms thrown out to the side, wearing worn tan pants and a white shirt.”3 And there it is: poverty as poetic imagery, murder as state-sanctioned spectacle, and the world of the visible and invisible converge for the imagistic consumption of the Times subject.

What is the work of enclosure that proximity engenders? How have viewers been trained to see, in the sliver of space between one person and another, contemporary photographic elision and mortality’s hyperpresence? “They, we, inhabit knowledge that the Black body is a sign of immi/a/nent death,” Christina Sharpe writes in In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, and with this immediacy comes a violent repetition, a fluid temporality, and a discursive trajectory of movement and stasis.4 For what audience are these images constructed? What progress do they refuse? In this book, I have moved between temporal elongation and quotidian fragility to understand how global obsolescence is articulated through photographic and black embodiment. How might contemporary photographic practices refuse this?

We know that discarding through ocular dismissal happens with the click of the shutter. Because the violence has already been done by external entities, (riot, famine, disaster, war), viewers can participate in multiple and repetitive acts of bodily unprotection. To observe and not interfere. This raises the question, What if observing is interfering? What if it inflicts violence through its guise of innocent witnessing, of passive participation? This is what it means to exist on the periphery of photography, on the margins of citizenship and belonging. Revisiting past grievous harm is also what it means to dwell on the cusp of a new century.

I have thus far argued that the proliferation of photographic imagery works to solidify antiblackness through a multitiered apparatus of the visual. Because this apparatus includes photography, there are particular questions the genre requires us to ask, just as there are ways of seeing and being seen that transcend the photographic (even within the realm of photography). If these documentary “scenes of subjection” exist devoid of the attendant historical mechanisms of imperial violence, they can appear to illustrate black obsolescence as destiny. Saidiya Hartman writes, “The emphasis on the joining of race, subjection, and spectacle is intended to denaturalize race and underline its givenness—that is, the strategies through which it is made to appear as if it has always existed, thereby denying the coerced and cultivated production of race.”5 Mortevivum is a scene of subjection that heightens the role of spectacle in the undermining of blackness. A photographic phenomenon that reframes sight.

Documentary Impulses and the Archive

Newspapers participate in the production of the everyday, and the tactile materiality of a newspaper is terminal as soon as it touches your hands. The ease of disintegration, the potential rips and tears, are part of the narrative of communicative obsolescence that produces its own othering. What is solidified through an apparatus of information gathering that ends up in the trash the day after it is considered brand-new? Photographic images. These images are their own genre of legibility. Over time and through thematic repetitions, viewers are trained to align the expectation of death with photographed black subjects—a discarding of a different kind. This is where the work of the contemporary begins.

Sentiment regarding Haiti cements itself during and after the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804). Something about the possibility of black self-governance could scarcely be produced visually without the undertone of dread. Black labor as a conduit to freedom made manifest the false biblical justification for transatlantic slavery. But black subjectivity is not the goal, and this is how we must reckon with the contemporary iterations of “framing” that can contain sight.6

When Haiti turned the empire inside out with its revolution, it coupled modernity with black freedom. We are still grappling with the visual meaning of the event. In The Disciplinary Frame, John Tagg explicates the utility of the photographic image. “The Camera is, then,” Tagg contends, “a place to isolate and discipline light.”7 If we extend this disciplining, then light is both literal and figurative. And photographs are one tool among many to extend imagined subjectivities, and to contain and corrupt those that resist temporal location.8 “Archives assemble,” Michel-Rolph Trouillot writes, and “their assembly work is not limited to a more or less passive act of collecting. Rather, it is an active act of production that prepares facts for historical intelligibility.”9 Contemporary viewers of photography assume, on a fundamental level, that they know Haiti, and that they have known the country for quite a while. What we must interrogate is the temporal layering that creates an air of expectation in opposition to the concept of black sovereignty. The assembled archives open out onto the visual field of ocular refusal—antiblackness as a participatory photographic endeavor.

Multiple external interventions, the overthrow of an imperialist regime, and the (financial/political) repercussions of these actions are enveloped in the visual iconography of Haiti. Underneath this iconography is the external pursuit of black failure and the repetition of the imagined permanence of this failure. Of each of this book’s geographical locations, by far the vast majority of images of suffering, death, and loss are from Haiti. This, itself, is telling. Nearly one million Rwandans were murdered during the genocide in 1994, and yet the media images from the nation were scarce and not evenly dispersed. What is it about the small Caribbean nation of Haiti that fractured white supremacist visions of empire? How did the promise of slavery’s totalizing capacities engender such imperial refusal that Haiti’s revolution was France’s melancholy—and America’s great fear? To understand a late contemporary global white gaze set against the first black republic to emerge from a history of transatlantic enslavement, we must work our way backward, before the invention of photography but after the invention of blackness.

Analog Vulnerabilities

With the tactile fragility of film, we can explore photography’s linear motion (shutter, negative, exposures) alongside its atemporal arc (landscape, location, form). Haiti’s revolution, which occupies a hierarchy in the visual register of restricted decipherability, becomes something of a photographic panopticon. It is a place/event through which the Western world surveils black resistance beyond the boundary marker of Haiti, but with the revolution as a triggering afterimage. Relegating the nation to a circular framework of failure is the “archive that assembles,” and a doubling mechanism that finds its footing in the presumptive articulation of meaning that the invention of photography, from daguerreotypes to its swift mechanical improvement, would not be impossible without the industrial revolution. Photography, then, was invented in Haiti by way of France, through black laboring bodies.10 What might it mean to think of photography’s invention as a precise by-product of a slave regime so mired in the violence of capitalist pursuit that revolutionary overthrow escaped the depths of consideration? Like a gelatin silver print without a negative trace.

The trace, though, is there. It is prephotographic and postvisual. It is a coercion of imagistic intention that must be negotiated atemporally, lest the potency of the moment shift out of focus, unable to be retrieved. Sentiment organizes the structure of political meaning as a photographic loop of imperialist failure, wrapped in the violence of racial indifference. What a white, class hierarchical visual engagement precipitates is the imagistic deterioration of black subjects, facilitated by an external world order that wants this desperately. Haiti is the visual field upon which melancholy mediates blackness through modernity’s extended hands. The emotive labor of violated black embodiment is in the visceral retrieval of its figurative capacities. Viewers can imagine black people both within and beyond the body’s utility. To see what is not there and imagine flesh continually removed from its corpus. An emphasis on the extended performance of the body places Haiti beyond the boundary marker of sovereignty, anxiously waiting for permission to enter its place in history. Newspaper imagery reinforces the desire of its intended readership: white subjects. In the context of slavery and corporeality, Saidiya Hartman writes, “If the black body is the vehicle of the other’s power, pleasure, and profit, then it is no less true that it is the white or near-white body that makes the captive’s suffering visible and discernable.”11 As with the intervention, American soldiers, many of them white, produce the political vision of the moment. This is a moment filled with shadows, dark undertones, and subterfuge.

Shadowed People

Shadows are an important photographic currency. Projections of shapes and figures there and also not there, they are abstractions of form, embodiments with distance, and ghostly matters with the inference of past trauma. They necessitate a certain proximity to conform to the mandates of visuality—a certain mathematical trajectory of both figure and symbolic referent. Critical race theorists have wrestled with the permanent shadow cast upon black subjectivities—a shadow that implies a form of doubling death. In Raising the Dead, Sharon Holland navigates this particular terrain “for those beyond the periphery, beyond even a language of the margin, for those literally ‘outdoors’ and therefore dead to others.”12 In the repetition of shadowed figures against a wall in Port-au-Prince, we see the juxtaposition of “we” and “they,” as the only figure visible is the armed American soldier seemingly providing the barrier between sovereign neglect and imperial protection. Although observing and not interfering, journalist Rick Bragg imagines the presence of the US Army as one of all-encompassing salvation. “The American show of force was intended as a clear message to the de facto dictatorship of Gen. Raoul Cèdras: No more brutality.”13 No more brutality . . .

Shadowed people. AP Photo / John McConnico.

This “show of force” is one that plays chess with history, marking the United States as the arbiter of global order within the continued primal chaos of the darker world. Frank Wilderson demarcates the space between racialized enslavement and the prison industrial complex, a distance that is not as wide as it may seem. “From the incoherence of Black death,” he writes, “America generates the coherence of white life.”14 These are images that seem to say: As they come apart (fragment), so shall we coalesce (come together). In the temporal elongation that reconfigures the terms of unbelonging, a still photograph intimates movement, even if that movement is a dead walking. This modulation does not neatly correspond to Ariella Azoulay’s rendering of the photographic force of the concept. So when Azoulay contends, for instance, that “photography, at times, is the only civic refuge at the disposal of those robbed of citizenship,” I want to trouble the waters of this when it is not the case.15 For the people whose lives are constantly coded via a discourse of unrest, who, starved or slaughtered, offer something unique and necessary to the viewing subject, there may be another contract at play, one that fails to lend itself to a process that is inclusive of blackness without violation.

In Other News

Days after the aircraft carrying the Rwandan president and the president of Burundi was shot down in Kigali in early April 1994, the New York Times mentioned the evolving genocide on the front page of the newspaper. Under the headline “Terror Convulses Rwandan Capital as Tribes Battle,” there is a universe, one that is constructed as an enclosure, a black-on-black crime spree resembling a “tribal battle.” In this construction, there is the palpable absence of empire, the obfuscation of Rwanda as a former German protectorate, the invisible tentacles of the Belgian regime, and the muted presence of the United States as a world leader tasked with responding to human rights violations. Instead, the sliver of space occupied by reporting on the genocide focuses on messages from French officials on the ground and offers very little in the way of understanding what is taking place in the small east-central African country.

Legible mostly as gruesome aftermath corpses, living survivors were disappeared within media coverage that was a situational failure. Privileging dead bodies over living survivors, newspapers and magazines marked the country as a “heart of darkness” from which there is no return. Judith Butler writes, “The body implies mortality, vulnerability, agency: the skin and the flesh expose us to the gaze of others, but also to touch, and to violence, and bodies put us at risk of becoming the agency and instrument of all these as well.”16 Are we attuned to this mortality, vulnerability, and agency only when it is untethered from blackness? Can we see it in the dark?

Cover page of the New York Times, April 9, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International.

The Interim

Days of protest, marching, and violence mark the removal of Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The New York Times coverage of the intervention illustrates this in graphic detail. On the last day of September 1994, the newspaper’s front page had, as its central image, a photograph of a crowd of Haitians at a rally in Port-au-Prince. Three dead bodies can be seen in the center of the image, surrounded by witnesses—friends and relatives of the deceased—who gather around the horrifying sight. On the far right a man faces the direction of the camera, his mouth agape, his face filled with anguish, and his hands gesturing toward one of the bodies, which is that of a young man. “A Haitian man screamed in mourning over the body of a friend minutes after an explosion in Port-au-Prince,” the image description reads. Screamed in mourning.

It is difficult to quantify how often facial expressions and bodily gestures made by black people are then misread and/or ignored by white viewers. A cultural rift, maybe, but one that has been rehearsed as a refusal of regard—an eagerness of denial writ visual. A racial apparatus of the eye. “Screamed in mourning” is one way to mute the presence of rage, to siphon anger in the quest for visual obliteration, and to create the thread of destiny out of a national crisis. As with numerous other documentary images published in the Times, this one has no photographer attribution. However, there are photographers present in the image. Their telephoto lenses and press passes tell us something about the history of imperialism and conquest that their photographs work to reinforce. “Screamed in mourning” is an abstraction of sight that ignores the indexicality (hands pointing) of the man’s gesture. This witness is the only reason the photograph is on the cover of the Times. This man’s anguish is what propels the framing of the photograph and the document’s utility as an addendum to the article.

Cover page of the New York Times, September 30, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International. This image has been altered from its original form.

Five days earlier, on September 25, a dark image shows US marines “subduing two Haitians” after a skirmish in which the marines killed eight people. “Details were sketchy,” Eric Schmitt’s article reports. The photograph provided by the Associated Press is sketchy as well. Two (maybe three?) soldiers are in the process of “subduing” men who are on the ground. Everything is black. The image is difficult to see clearly. This, of course, is part of the point. Chaos lives in the interstices of the dark, or so we are constantly told. People, places, cultures, and nations—all are utilized to demarcate the sense of “not there” and “not us” that dominates extrajuridical US policy.

Marines subduing two Haitians in Cap-Haitien. Courtesy of PARS International. This image has been altered from its original form.

Cover page of the New York Times, September 25, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International.

That we have no photograph of the Haitians killed by marines splayed across the front page of the Times is one indication that mortevivum necessitates an absent index. There is no single person to point to in order to say, “this is the person who committed the act.” No death dealer among all this death. So instead we have spontaneous slaughter that reifies the law of the corporeal as if an act of nature swept people off the earth. From “screamed in mourning,” we now have “nothing to see here.”

This leaves on-site witnesses with the impossible task of seeking and deciphering the occupation of space that public acts of violence engender. And because these are public acts, they cull the register of engagement forcefully, leaving gaping holes of understanding to hover unencumbered. The daytime photo of people surrounding dead bodies and reacting, in real time, to the horror of the emergent scene is replaced by the visual of a (covert?) military action that produces multiple deaths that occur (we are to assume) outside of the frame of the photograph. Death in the dark or death in the light—the images illustrate how little this matters for black subjects. The matter, according to the reiterated set of images, is black death. Of the dozens of image choices editors of daily papers have, how is it possible that the more inhumane the photograph of a black person, the quicker the rush to display it? Antiblackness frames this photographic interface, its arc and reverberations, across temporal, national, and discursive fields. Like “screams in mourning” when the mourners are perpetually black.17

The Other Side of the (White) Visual World

On what was the 904th day of the siege of Sarajevo, the New York Times featured a photograph of a hospital worker at a Kosovo Hospital calmly folding sheets for use at the facility. The image description reveals that the hospital has lost its electricity during the Bosnian War (1992–1995), necessitating the manual labor of workers like this one to sustain its operation. There is something organized and peaceful about the photograph. The framing functions as an enclosure, with several Bosnian subjects existing within the protective (albeit cloth) boundary, seemingly removed from the onslaught of the violence taking place outside. The man in the forefront of the image is not looking at the photographer, but the man standing to his immediate left is doing just that. He looks in the direction of the photographer or just beyond them. Perhaps his eye is focused on someone or something outside the frame. It is not easy to tell. There is at least one more person who is present in the photograph. A forearm in motion.

The image accompanying the Times article is detached from the article’s headline (“Sarajevo’s Unending Travail”), but not completely. Roger Cohen’s piece emphasizes how much (or how little) progress has been made by the Bosnian government in the war against the Serbs. Cohen asks, “Is such a long war—undermining Europe, destabilizing the Balkans and straining transatlantic relations—acceptable to the United States?” The political investment in what is “acceptable to the United States” frames the image that accompanies the piece in contrast to the dozens of images of dead bodies connected to Haiti’s political upheaval.18 The difference between newspaper coverage of Bosnia and coverage of Haiti functions to effectively differentiate the space between black fungibility and white value. What Gloria Wekker refers to as white innocence pervades the visual offerings that occupy media imagery.19 By the end of the twentieth century, viewers are fully entrenched in the visual training they have received.

Days into the newspaper coverage of the intervention in Haiti, the New York Times international section is marked with reporting that concerns the siege in Sarajevo and the consequent political interests represented by the United States. Cohen writes, “The end result could be a dirty little war in Bosnia, with America quietly supplying arms to the Bosnian Muslims, Russia quietly supplying materials to the Serbs through Serbia, and the border secured against any wider conflagration.”20 There is something worthy and retrievable here, something able to be made legible and it doesn’t have to announce itself to register. “The invisibility of whiteness as a racial position,” Richard Dyer laments, “is of a piece with its ubiquity.”21 Ubiquity functions here in its visual disavowal, the empty space between object and subject that viewers navigate, aided or not. Dyer continues:

Death may in some traditions be a vivid experience, but within much of the white tradition it is a blank that may be immateriality (pure spirit) or else just nothing at all. This is within the logics of whiteness even if it is not at the forefront of white identity. White people have a colour, but it is a colour that also signifies the absence of colour, itself a characteristic of life and presence. In the transparent representation of the culture of light, the white face has to be read in the blanks on the paper or screen. To be positioned as an overseeing subject without properties may lead one to wonder if one is a subject at all.22

Interior page of the New York Times, September 25, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International.

To leave whiteness on this mortal coil is to engender a vulnerability that whiteness refuses to occupy. It is to lay bare the contradictions born of binary modes of seeing, and it is a difficult endeavor. As a result, documentary images, particularly as they exist in the New York Times and other periodicals, reinforces the idea that whiteness and death are intermingled, but also projections of cultural refusal. So much so that white vulnerability is rendered precious and black fungibility mundane. What is the proof that white people die? This is an archival question still yet unanswered.

September 1994 was a difficult month to be black within the pages of the New York Times. Over the course of that tumultuous month, the newspaper featured numerous corpses in various states of decay, nearly all featuring a body marked by its vicarious distance from the eager eyes of the viewer. The removal of the Times subject from the violation on display does a tremendous amount of cultural work. For the suburban American subject, gifted with the relative and physical distance of belonging, the images can sadden and disturb, enlighten and enrage. Given the range of possibility, it is little wonder that the temporal multiplicity of blackness as woundedness exists so fully as to be commonplace. What we can gather from the pioneering scholarship in existence for the last hundred years on lynching is that this phenomenon of public violence has a tangible linchpin: the keepsake. In a desire to revisit the experience and a communally-inspired quest to share the occasion with others, photographs and postcards became key to this display. The difference now is the keepsake is delivered to our homes daily or viewed privately over the internet or retrieved without the viewer having to leave the comfort of the domestic sphere.

In a September 26, 1994, image from the US intervention, a group of mourning women dressed in white stand over the corpse of a loved one lying in a Port-au-Prince street. They seem only tangentially aware of the multiple photographers clamoring together to capture the moment of unearthed anguish. The shadowed people are the ones with the power. Their lenses repeat a story of conquest and articulated self-destruction, as the sun’s position casts their silhouettes on the ground close to the dead man’s body.

Two hundred years after the invention of photography, it is still absence and hyperpresence that naturalizes and delineates. Dead black bodies normalized through the absence of dead white bodies; “that has been” replaced by a lulling “this should be.” Given photography’s conflicted relationship with representing the other, it is no wonder that its earliest resonance coincides with an intractable difference—negative to positive—an optical opposition. “Being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country is a quintessential modern experience,” Susan Sontag tells us.23 “In fact, there are many uses of the innumerable opportunities a modern life supplies for regarding at a distance, through the medium of photography—other people’s pain.”24 How might we attempt to address the trauma black people experience while they grapple with humanity so fraught that its very visibility is a problem? “Acts of remembrance,” Edwidge Danticat writes, “like pieces of art, can also surface out of daily rituals, even interrupted ones. A place setting left unused at a dinner table. An oversize shoe into which we slip a foot. A tearstained journal in which we scribble a few words about unclaimed bones.”25 But what of a visual politics of remembrance that insists upon the destruction of black subjects? How can this mandate be undone?

Interior page of the New York Times, September 26, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International. This image has been altered from its original form.

For the short period in which US soldiers were stationed in Port-au-Prince, the cover images of the New York Times engendered the idea of Haiti as death knell. In a chaotic barrage of violent images, the narrative of impossible black governance takes on new meaning at the end of the year, particularly as South Africa is months into its new nationhood. From the earliest black republic in the western hemisphere to the most recent nation to renew itself after decades of white supremacist juridical rule, Haiti is a nation of contrasts, reconfigurations, and renewals.

The body of the soldier is shadowed to a silhouette, but his automatic rifle is not. The weapon is clearly displayed, leaning diagonally across the soldier’s knee, in close proximity to a small child sitting against a walled barrier. Her arms are crossed and resting on her knees. There is a straw sun hat on her head that is slanted to her right. In an extended reading of this image, the viewer, it must be presumed, is encouraged to imagine the future of Haiti (as represented by the child) as one that is always under the gun, a history that collapses two hundred years of independence into a single referendum on the nation’s fraught sovereignty. That this intervention, the second major occupation of Haiti by the United States, is barely noted in the newspaper should strike one as odd, and yet documentary photographs endeavor to normalize military interference. It is as if Haiti is ever the small child, set against a barrier, waiting for an external paternalistic rescue. So both inexperience and imminent death stalk the photograph as it appears to the viewer. As with the majority of these swiftly taken shots, there is no name attributed to the photographed subject and no further information provided. A trace of photographic training (a Barthesian studium noir) operates at an angle, a slant that diverges away from black subjectivity. This slant facilitates a diagonal slope of care moving from invisible and omnipresent whiteness to ubiquitous but discardable blackness. That so many children are figured centrally in these images denotes the racial parameters of ocular investment assumed by Times readers and viewers. If, as Pooja Rangan asserts, “the prehistory of participatory documentary offers us one possible model for recouping the dialectical potential of the figure of the child,” then what does it tell us about the visual expectation of what Rangan refers to as “feral innocence” that operates “as fetish”26? Are viewers to be trusted with the bodies of others when there is so much at stake?

AP Photo / John McConnico, September 22, 1994.

The child’s right eye can barely be seen in the photograph. The left eye is completely obscured by shadow. The one eye stares out from the darkness and into the perception of light. Scholars of black and white photography have purposely tussled with binaries of light and dark, “good” and “bad,” and this is the inflection the image offers. What is the “bad” on view here? Is it conditional (the intervention), national (Haiti as a “bad” sovereign), generational (and the children suffer), or racial (blackness as imminent death)? Here, shadow (shade) demarcates the photographic space between object and subject as the rifle at the center of the image (the object) indexes the child at the far right of the photograph (the subject). Little room is left to say what is present outside the imagery of force and failure. Fragments of space are available to occupy the eye beyond the structure of this binary: Force that is necessary due to the elongation of national (read: racial) failure. Failure that has been destined since the founding of Haiti after the revolution. Force and failure bracket the imagistic engagement Haiti has with the media as this is the only narrative that has been allowed to prosper. External force and internal failure. The idea of revolution, of freedom, is repeatedly undermined.

Saint Domingue Gives Birth to Haiti

Haiti enters the visual field of the Atlantic world narrative under its former name, Saint Domingue. As contemporary historians have noted, part of Haiti’s deployment in the political imaginary is measured through the multiple crops the colony yielded for the empire of France. According to Laurent Dubois, “The livelihood of as many as a million of the 25 million inhabitants of France depended directly on the colonial trade.”27 This trade was then as brutal and corporeally divisive as the contemporary entrapments of “good intentions,” intoned by a visual relationship intimately encoded to show a nation in a constant state of upheaval. Before it was a modern site of imperialist deflection, it was the most profitable colony possession in the West—the bright light of early material and corporeal capitalism.28

In the way Haiti entered the global imaginary, it resembles the modern flashpoints of repeated engagement: a place and a people to fear, an infected and infecting populous (revolution, insubordination, disease, vodou, trauma), and the site of death on death. The specificity of the circumstantial is a large part of my interest here. Essentially, my aim in this book has been to use photography as a focal point of national and civic engagement postulating the viewer (Western, white) as the arbiter of inclusive humanity.

In the introduction to Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman speaks of those mainstays of racial violence in literature that “immure us to pain by virtue of their familiarity,” noting that “they reinforce the spectacular character of black suffering.” Of the pained body of the enslaved, she writes: “Are we witnesses who confirm the truth of what happened in the face of the world-destroying capacities of pain, the distortions of torture, the sheer unrepresentability of terror, and the repression of dominant accounts? Or are we voyeurs fascinated with and repelled by exhibitions of terror and sufferance? What does the exposure of the violated body yield? At issue here is the precariousness of empathy and the uncertain line between witness and spectator.”29 It is in this narrow space between witness and spectator that our imagistic sensibilities take form, cultivating the photographic rupture between the living and the dead, the subject and the subjected. W. E. B. Du Bois’s famous query—“How does it feel to be a problem?”—has, by the end of the twentieth century, evolved. The question is now, “How do we solve the problem of black people?” And the answer is: visually. In other words, on the cusp of the twenty-first century, there remains a desire to see black people in a constant state of impending death. And photography delivers, aided by white supremacy. Christina Sharpe writes, “For if we are lucky, we live in the knowledge that the wake has positioned us as no-citizen,” and from this position something new may be deciphered. Something new can emerge.30

In the days forward, scenes from the intervention inflect the flashpoint of engagement from a very specific emotive register. An absence of interest in the health, safety, and well-being of Haitians presents itself as a cartography of the ocular. This cartography narrows the field of vision for the Times subject, as blackness is easily consolidated into mortevivum—a proximity to death repeatedly rendered photographically. In the production of this default subjectivity, photographs mediate the space between citizenship and sentiment, and traverse this ground by following a road previously paved for white comfort and black suffering. No matter the geography, the comfort of the viewer, assumed to be white, is what foregrounds these images. This comfort creates silos of safety that are framed by the reinforced citizenship of global whiteness. Haiti is the figurative focal point that opens out onto modernity—the temporal aperture allowing light to enter but never self-illuminate. Illumination, as it has been articulated in a white supremacist production, is the province of the white West, and nowhere/no one else. As they fall apart (disintegrate), so shall we coalesce (come together). It all begins with Haiti.

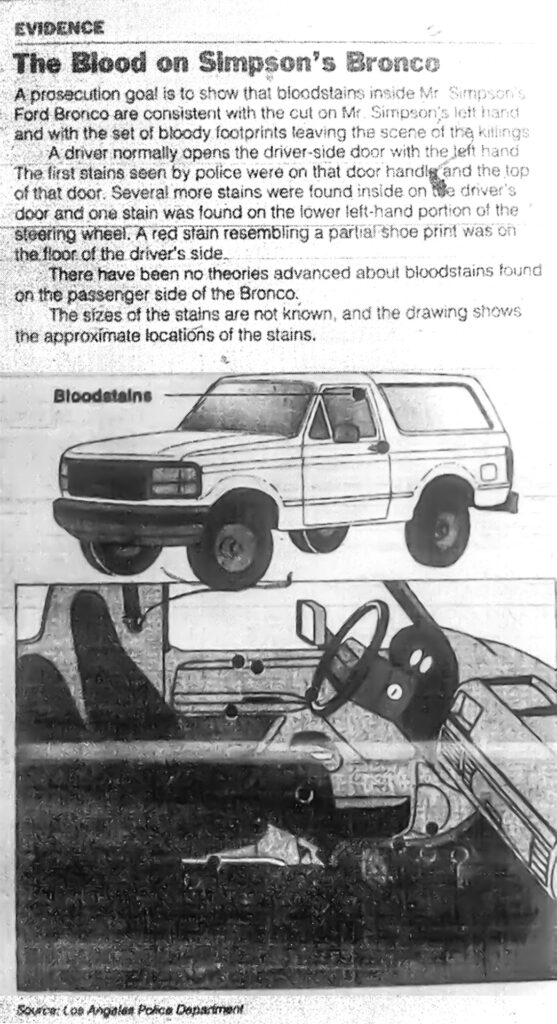

In the days that follow, the New York Times will feature rhetorical replays of the tale of a white Bronco and a black defendant, news magazine covers with corrupted and manipulated photographs will be crafted to further darken the lack of distinction between race and extreme acts of violence. This will all happen in the span of the same month of registered visuality and display.

The months of inquiry into what will be eventually called the “trial of the century” occupy prime real estate in the Times. For the future trial in criminal court, People v. O. J. Simpson, race, class, fame, and violence seem to coalesce into a veritable circus of rage and entertainment. During the start-up to the trial that would dominate news media outlets for most of 1994 and 1995, in which Simpson would be acquitted of double murder, much was made of the circumstances surrounding the case, its famous defendant, and the racial discord engendered by the allegations. During the year, multiple pages were devoted to reporting on the murders and analyzing the evidence to be presented at the trial while synthesizing concurrent discussions about race in America. Simultaneous and astounding, the timing of the articles coincides with the intervention in Haiti, so much so that there seems to be a cleanly distributed overlap between the island nation’s destiny and Simpson’s.

O.J. Simpson’s Ford Bronco is entered into evidence. Courtesy of Los Angeles Police Department.

A visual stitching of documentary alignment becomes useful in its aggregate form. Images of mourning, like those appearing in the New York Times, highlight the temporal infrequency employed by viewers when those imbued with sympathy are visually set against those who are to engender no such thing. “These journalistic photographs,” Barthes contends, “are received (all at once), perceived. I glance through them, I don’t recall them; no detail (in some corner) ever interrupts my reading: I am interested in them,” he continues. “I do not love them.”31 He does not have to “love them,” but what is striking is that Barthes finds these photographs only of momentary interest, and never more than an aberration of investment. It is here, in the space of emotive extensions of care, that blackness is reified as a glance and a glance away. Regard and disregard. But the art of black study, the effort to find and reinforce a ritual of looking that produces the very intentional practice it uses to sustain itself, this must be the way forward.

Days of mourning follow the public display of dead bodies photographed and printed on the cover of the New York Times. The dead appear to be subjects worthy of investigation, but in truth they are objects of discourse, of dispossession. Sporadic information is provided about the dead and occasional notifications of funerals given. Family members are photographed in black, coming from or going to funeral processions. Amid a string of chaotic images connoting the spontaneity of national violence occurring in Haiti, there are interspersed scenes of gathered mourning practices presented for the viewer. Between the clarity of images of the dead and the photographic subterfuge of US military practices abroad, news media outlets curate this cartography of the ocular, which is centered around deserving deaths and invisible lives. Documentary photographs invest the viewer in a myriad of emotive mechanisms designed to bring an event into perspective. It matters that this perspective is a practiced loophole into which antiblackness slips. A space for nonblack pontification and black resistance, most of which happens as viewers sit with the quotidian task of news gathering. In the documentary apparatus of photography, eyes invested in the particularities of truth-making settle on a theme. The result is a transcription of antiblackness rendered visual.

“No Graphic Warning”

One month after the massive earthquake that took place in Haiti on January 12, 2010, news media outlets refused to show images that might further upset the viewing public. Interestingly, these images were of the accident that killed a Winter Olympics luge athlete from the nation of Georgia, and not of the hundreds of thousands of Haitians killed by the earthquake. Viewers who watched the luge video were outraged by the sight and wrote in to various media outlets so that the video would be removed. The earthquake in Haiti, seen by tens of millions of Americans in an eerie loop of repeating imagery—corpses lining city streets, maimed, wounded, and semiconscious Haitian citizens recovering from severe trauma—did not elicit the same outrage. And if it did, it failed to move the media to the same ethical consideration of the dead.

For days and weeks after the accident at the Winter Olympics in Vancouver, viewers questioned the ethics of looking as it pertained to Nodar Kumaritashvili’s luge crash. Viewers left responses to a question posed by Newsvine: Should the luge video have been aired on TV? A full 50 percent of survey participants said the video should not have been shown. With comments ranging from “A horrific video for loved ones & friends to have seen” to “if it were my family member (or even me) I wouldn’t have wanted the world to see it,” people were disturbed that the video was shown at all, never mind multiple times.32 On the question of the earthquake in Haiti, there is no such dilemma. No “loved ones” or “friends” to consider. No family members to grieve for the dead, survive them, or mourn in private. There is no viewer backlash once documentary images proliferate in the media. It’s worth examining why death and blackness are aligned via information-gathering sites that purport to bring news to the masses.

Contemporary videos of black people shot to death by police, wrestled to the ground and suffocated, or tased to death are ubiquitous in the United States and beyond its borders. Incredibly, even when the friends and family members of the victims of these public deaths request that photos and video footage of their dead bodies remain out of the public domain via social media, these requests are aggressively ignored.33 Is antiblackness an ill that documentary impulses expose without the possibility of resolution? Can geography provide the template of meaning-making where black subjectivity can live and breathe without the threat of obliteration?

For Ariella Azoulay, what she terms the civil contract of photography “is a way to delineate part of the newly constructed space of civil relations that has been opened—and even necessitated—by photography.”34 For Haiti, this “newly constructed space of civil relations” is actually centuries old, but the advent of photographic practices extends the vibrancy of this familiar paradigm of destabilizing epistemology. Simply put, empires (France, Britain, Spain, the United States) participated in processes of mortevivum: rigidly discarding and objectifying based on a prescribed manipulation of ocular intimacies. They did so before the advent of photography, and therefore may have produced a predetermined negotiated proximity that provided the racialized gaze a viable (violateable) silver gelatin scapegoat. A corporeal catastrophe, as Azoulay might term it, that unfurls and repeats in a cadence of failed black self-governance.

And so it might be said that Haiti registers photographically to replace slave success (and revolutionary overthrow of the empire) with modernity’s revenge: a visual culture determined to illustrate, with devastating immediacy, how little that has meant to the world. Although two hundred years of black independence has bored a hole into the hegemonic currency of the West, it is a hole filled with photographs of nationhood as failure. As an imagistic site of perpetual ruin, Haiti’s relationship to the larger world falls under the thumb of what Ann Laura Stoler terms imperial formations. These formations are not tethered to a single, recognizable empire; rather, they are “states of deferral that mete out promissory notes that are not exceptions to their operation but constitutive of them: imperial guardianship, trusteeships, delayed autonomy, temporary intervention, conditional tutelage, military takeover in the name of human rights and security measures in the name of peace.”35 Haiti’s status as a nation of the formerly enslaved and nonwhite eliminates its very capacity to be seen as a sovereign power. Because Haiti’s emergence as a sovereign nation coincides with US imperialist missions (also involving enslaved peoples) that were easily threatened by the frightening concept of black revolution within or without the empire, a popular and enduring refrain emerges: that catastrophe follows all efforts to resist paternalistic protection.

Imperial dispossession is a photographic practice, an existing archive of destruction, enslavement, and scopic control. Its afterimage is a series of textual offerings that foreshadow the punitive return facilitated by the start of the Haitian Revolution. We are entering the third century of misaligned aggression: financial, political, social, historical. Archives assemble. Let us also consider the visual narrative of revolution that, curated and maintained for over two hundred years, resists consistent attempts at reinterpretation. As news media outlets merge temporalities, as they pertain to black agency and resistance, the productive deployment of sovereign failure is an antiblack photographic refrain. The viewer’s projected investment extends the proliferation of the maimed (or contained) black world subject, offering the viewer the ability to slaughter with the eye those who have been foisted out of time. This is what it means to live perpetually in the psychic photographic space of black peoples’ demise. A history of violence that repeats itself. A living thing, a dead offering.

Note 1

Mary Renda’s book Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) traces the 1915 intervention in Haiti through the lens of US imperialism and paternalistic impulses. She writes in part, “Formally, the United States was at peace with Haiti. Consistent with the official state of affairs, paternalism conferred on the United States the status of an elder brother, in Haiti on a mission of paternal care and guidance” (135).

Note 2

Barthes is interested in the space between has been and is to be that photography seems particularly suited to manipulate. In an extended discussion of the promise and the perils of photography, Barthes muses: “Photography transformed subject into object, and even, one might say, into a museum object: in order to take the first portraits (around 1840) the subject had to assume long poses under a glass roof in the bright sunlight; to become an object made one suffer as much as a surgical operation; then a device was invented, a kind of prosthesis invisible to the lens, which supported and maintained the body in its passage to immobility: this headrest was the pedestal of the statue I would become, the corset of my imaginary essence.” Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 13.

Note 3

John Kifner, “Police Crush Rally as American Troops Watch,” New York Times, September 21, 1994, 1.

Note 4

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 71.

Note 5

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 57.

Note 6

Haiti is particularly pertinent in this regard, as most of the news information contemporary readers have of the nation situate Haiti in relation to chaos and inconsistent political leadership. Erica Caple James writes in part, “A long tradition of misrepresenting the Haitian nation and its culture, especially on the part of Westerners, complicates many recent as well as older depictions of the country’s plight.” James, Democratic Insecurities: Violence, Trauma, and Intervention in Haiti (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 9.

Note 7

John Tagg, The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 1.

Note 9

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 52.

Note 10

Laboring bodies on the plantations of Saint Domingue brought wealth to France before and even after slavery ended. See Catherine Porter, Constant Méheut, Matt Apuzzo, and Selam Gebrekidan, “The Root of Haiti’s Misery: Reparations to Enslavers,” New York Times, updated November 16, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/20/world/americas/haiti-history-colonized-france.html.

Note 12

Sharon Holland, Raising the Dead: Readings of Death and (Black) Subjectivity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000).

Note 13

Rick Bragg, “Mission to Haiti: In Port-au-Prince; Cheers and Signs of Relief as Beatings Subside,” New York Times, September 23, 1994, A12.

Note 14

Frank Wilderson III, “The Prison Slave as Hegemony’s (Silent) Scandal,” Social Justice 30, no. 2 (2003): 18–27, 23.

Note 15

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2012), 121.

Note 16

Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (New York: Verso, 2006), 26.

Note 17

In a New York Times editorial, linguist Michel De Graff wrestles with the lessons he was taught to absorb concerning his native tongue, Kreyòl. De Graff writes, “I consider the description of Haiti as the poorest nation of the Western Hemisphere to be a gross misrepresentation; Haiti is, rather, the nation most impoverished by the effects of white supremacy. The emissary of Charles X imposed an insurmountable financial ransom, but the French educational model, a supposed war bounty, was every bit as brutal: a linguistic ransom, a powerful tool for mental colonization. Haiti’s French-speaking elites, who have enforced that mandate, have always lived as far away as possible—geographically, socially, culturally, religiously and linguistically—from the majority Kreyòl-speaking population. They have never created a system to adequately teach French to those who did not grow up speaking it. Instead these Haitian elites favor teaching in French—an option that’s guaranteed to multiply the privilege they already enjoy and to ensure that most of their fellow citizens cannot share it.” Michel De Graff, “As a Child in Haiti, I Was Taught to Despise My Language and Myself,” New York Times, October 12, 2022.

Note 19

Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

Note 25

Edwidge Danticat, The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2017), 56.

Note 26

Pooja Rangan, Immediations: The Humanitarian Impulse in Documentary (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 59, 47.

Note 27

Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 21.

Note 28

Profits from slavery in Saint Domingue sustained much of the nation of France for most of the eighteenth century and well beyond.

Note 32

The Newsvine survey is one of the few places where you can ascertain how people are processing, in real time, filmed accidents that involve people dying.

Note 33

After Michael Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson, Missouri, his family asked that images of his dead body lying in the street not be circulated via social media. Their requests were largely ignored.

Note 35

Ann Laura Stoler, “Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination,” Cultural Anthropology 23, no. 2 (May 2008): 191–219, 193.