The Empire

1the photograph—who you were— will be waiting when you return.

—Natasha Trethewey

Decades after he is imprisoned for subversion, Nelson Mandela is poised to be the first black president of the Republic of South Africa. The Sunday, May 1, 1994, front page of the New York Times features a photograph of Mandela looking serious and solemn, eyes slightly lowered as if deep in thought. Bill Keller’s article “The Man for South Africa’s Future” traces Mandela’s unlikely political trajectory from state prisoner to “president-in-waiting.” So much of the essay seems constructed to soften any imagined hard edges the reader supposes Mandela may possess. The soon-to-be president is called “the most practical of men.” Keller continues: “He is not unfeeling, but passion—even anger at what he has endured—does not drive him or distract him. He enjoys debate, but he is not a great philosopher or intellectual. He has principles, but he will bend them if they stand in the way of his objective—which, for the last half century, has been ending white domination.”1 With so much hinging on the unification of a postapartheid South Africa, offering Mandela as a “practical” man, one devoid of “philosophical” or “intellectual” diversions, aligns cleanly with a (white) readership necessitating “civilized” reactions to the savagery of white supremacy. Aided by an Associated Press photograph, Mandela’s eyes do not meet those of the viewers. There is an undertone of gravity in the image, as if the future president is attempting to take in the totality of meaning that his presidency symbolizes. Because of this, each visual gesture—the slight furrowing of his brow, the way his hands come together, open, yet clasped—is filled with fifty-odd years of symbolic meaning.

In those first few paragraphs of the New York Times piece, Keller also describes Mandela’s decision, soon after his release, to build a vacation home that is “an exact brick replica of the warden’s house” where he lived for months recovering from illness and where he met “secretly” with representatives of the state.2 This detail is important, for it situates Mandela as less of a threat to the status quo. Indeed, Keller marks the duplication of the warden’s bungalow as Mandela himself explains it: pure pragmatism. In the enclosure of a prison domicile, a narrative arc works to sustain an acceptable transition of power. The kind that many white people can find a way to live with as it is grounded in civility’s appendage: practicality. “The body is the place of captivity,” Dionne Brand writes, and Mandela’s imagined and real imprisonment is one he brings with him into postimprisonment, prepresidential shape.3 It seems vital (and subsequent New York Times articles reinforce this) that the preservation of white order remains even when the black majority has political control over the nation. Thus, while Mandela’s image offers us a contemplative and thoughtful visual representation, it shows a man holding the totality of a bruised nation in his partially clasped hands—an impossible human endeavor. One nation is dead, and another is born to replace it. But can life emerge out of such a violent death?

Cover page of the New York Times, May 1, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International.

Decades mark South Africa’s experiment with racial apartheid through photography, an ocular conundrum. From 1948, when the white supremacist National Party was voted into power, until 1994, when apartheid “officially” ended and Nelson Mandela was elected president, photography centralized the way the world learned about the violence that accompanied the apartheid regime. Because 1994 is a significant year in South Africa’s racial trajectory, Mortevivum opens here in this geographic space of fluctuating sovereignties mired in deep, interlocking histories. “In many ways,” Achille Mbembe writes, “our world remains a ‘world of races,’ whether we admit it or not.” Mbembe continues: “Although this fact is often denied, the racial signifier is still in many ways the inescapable language for the stories people tell about themselves, about their relationship with the Other, about memory, and about power.”4 Decades mark this terrain of “inescapable language” with the violence enacted by the apartheid regime and thus pull the viewer into the frame.

Gelatin silver prints created during this time present South Africa as a space of binary opposition: black and white, negative and positive. Something about photography’s originating construction (interior versus exterior) reinforces a racialized binary that gets played out symbolically. This chapter will ponder the presence (or lack thereof) of black subjectivity as it exists within the ocular space of mortevivum. Mortevivum is the photographic dividing line of death’s proximity to blackness that writers and cultural practitioners must continually negotiate. It is the “voyage through death to life upon these shores” that Robert Hayden’s poem “Middle Passage” presents as a thematic organizing principle of slavery’s life and slavery’s afterlife.5 Its conceptual refraction, sempervivum, on the other hand, orders the structure of whiteness as the visual corollary of a racial elongation of human life—the ocular production of the live forever. If whiteness functions as sempervivum, the logic goes, it can only do so by signaling or referencing its inversion—mortevivum, which has a register of default blackness.6

I take seriously Toni Morrison’s declaration that “slavery broke the world in half, it broke it in every way.” And in taking this seriously, I am invested in thinking about the world-altering mechanisms of transatlantic racial slavery and imperialism that are yoked together in order to upend the order of the world. Morrison continues: “You can’t do that for hundreds of years and it not take a toll. They had to dehumanize, not just the slaves but themselves. They have had to reconstruct everything in order to make that system appear true.”7 Colonial archives, oral histories, and legal documents bear out the horrendous nature of Atlantic slavery and imperialism. Furthermore, the place that white supremacy occupies in the world tells us something important about the force and the power of the need to “make that system appear true.” By the time photography was invented, racial slavery had become a fixture of the Western world. Photographs reinforce a hierarchical racial fantasy that slavery and imperialism exacerbated.

Etymologies

From the Latin imperium, meaning “to command,” we receive our current deployment of the word empire.8 In the context of South Africa, I am most invested in the definition that follows: “An extensive sphere of activity controlled by one person or group.”9 To command. The “extensive sphere of activity” structured around white supremacy made an empire out of whiteness and contained it in the movements and restrictions of groups of people over time. We have seen this before—namely, in the racial stratification of the United States, where for decades after the end of the Civil War (1861–1865), black Americans were regulated under a “sphere of activity controlled” by white supremacy. Their ability to live, to move about, to work, to own property or be autonomously rendered was constrained within white supremacist strictures, similar to its construction in South Africa. Here I aim my focus in this bifurcated direction between the United States and South Africa, and at the imagistic scaffolding that impacts imperial regimes structured by race but within national borders.

Gordon Parks, Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama, 1956 (printed 2012), High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Repercussions

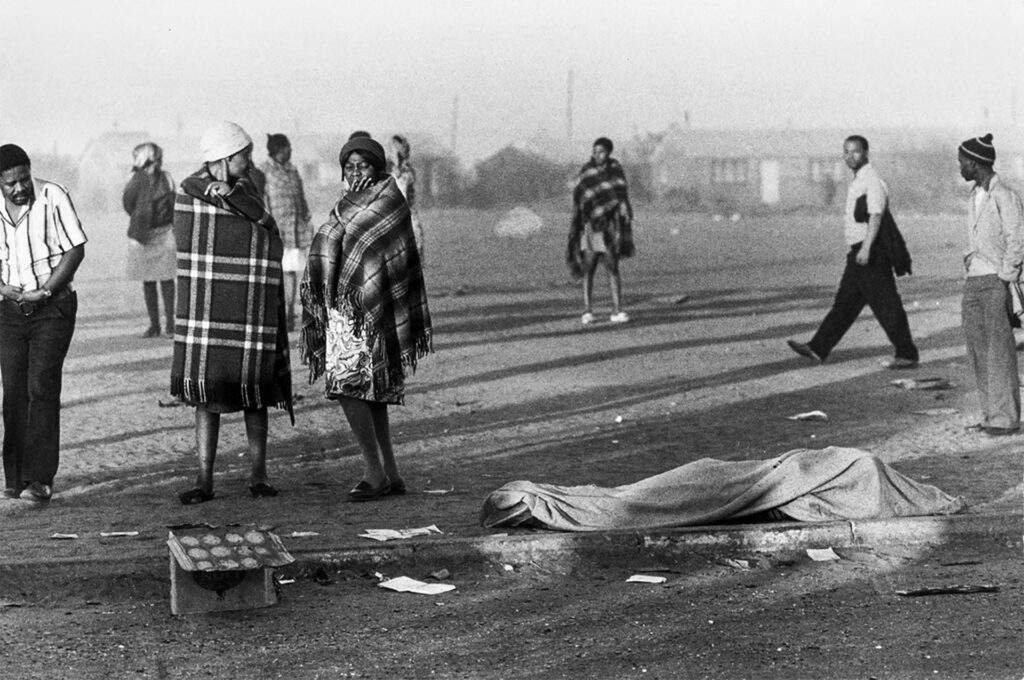

The past has a photographic history as well. In one iteration, found in Peter Magubane’s 1976 photograph Soweto Riots, we see two women standing near the left of the center of the frame of the photograph. They orient the eye of the viewer. The center contains nobody. But there is a body on the ground—someone no longer alive, but occupying space. Wrapped in plaid (Basotho) blankets, and each exposing one hand that emerges through the sleeve of space the blanket provides, the women stand. Someone has died the evening before this early morning shot was taken. One woman is turned away from the body; one is turned in the direction of the body. She looks down and over. The violence of the evening before is both indexical and evidentiary.10

Peter Magubane, Soweto Riots, 1976. Courtesy of the International Center of Photography (https://www.icp.org, archived at https://perma.cc/Z238-Q8JX).

Three men frame the outer edges of the photograph, providing it with corporeal margins—one on the left, and two on the right. One of the men directs his eye to the body on the ground, one gazes back at the photographer, and the last man turns his gaze away from both ocular possibilities. Together, their bodies center the two rows of women (six in all) encased within the boundary of the image. Ten people: nine living, one dead.

In Magubane’s photograph, we see an archive at work, and it is an image that reframes the intent of an empire within a nation. It is a scene of temporal fluidity, an intertextual vision of the layering of black unbelonging. In the photo, a group of black South Africans are assembled around a dead body after the Soweto protests begin taking place. Each of the people present attends to or avoids the sight of the body. The body itself is a problem—its placement in the image’s foreground, its status among the dead, and its presence in close proximity to those gathered about it. As the photo intimates, the space between blackness and death is so close that it is often impossible for Western practices of the ocular to tell the difference.

A visible tether joins the men and women in the image to the person who has just recently passed from life to death. This is what renders the photographic scene with its taut emotive extension. Not one person in the image will voluntarily cross the threshold of this death, a subjectivity that Giorgio Agamben might call killable but not mournable.11 Stopping inches away from the body, they address it as its own cruel visual display. They both recognize and resist the demarcation of what Saidiya Hartman would call their photographic fungibility, and the imprint of too many inculcations of temporal duress.12 The image is useful to ponder the present absence of blackness photographically, and within the ocular space of what I call a cartography of the ocular. This cartography has layered antiblack dimensions: the seeming absence of empire, the collapsing of historical exclusions, and the repetition of racial subjections. This joins black Americans and black South Africans under a similar rubric of photographic removal, where a racial hierarchy presents itself invisibly while enforcing itself so violently.

Once black bodies are removed from lynching photographs, the question remains: Who were these people and why were they so eager to be photographed? For Ken Gonzalez-Day, “The history of lynching demonstrates that without a legal code of law, justice is little more than fleeting passion—mob rule.”13 And this is most often how lynchings are written about, as demonstrations of vigilante justice, a way for community members to right wrongs that have been done in the glaring light of day. This is all tangled up with race, class, gender, and geography in the United States. And it has a back history as old as the nation itself. Tina Campt writes, “The materiality of the photo secures neither its indexical accuracy nor transparency; it leads us to question it instead.”14 In this case, these questions go beyond the details of the photograph and through the cultural arena of which they are a part. What does Indiana in the 1930s have to tell us about how racial mores evolved in the decades that preceded it?

Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, Marion, Indiana, August 7, 1930. Courtesy of Getty Images. This image has been altered from its original form.

Photographic Histories of Violence

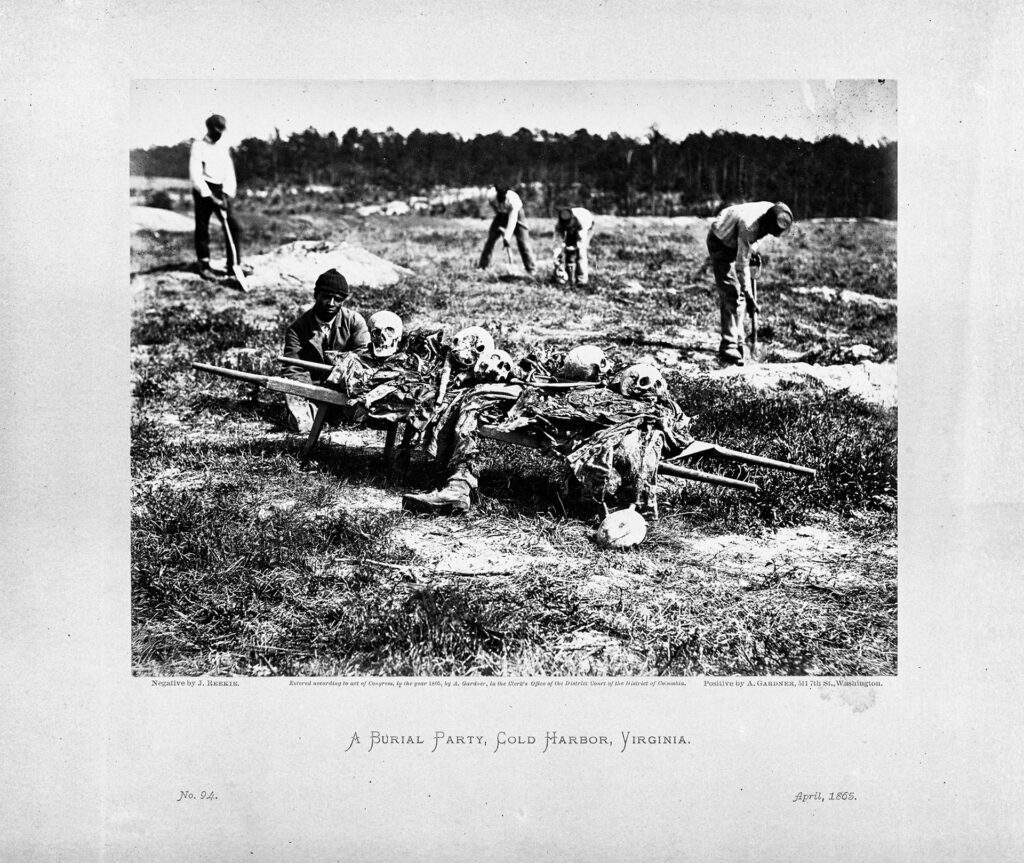

Five black men fill the photographic space with the visible labor their bodies represent. One stands, and three are bent over as they negotiate the Virginia earth and the burial task they must perform. In the forefront of the image, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the seated black man and the skeletal remains of American Civil War soldiers alongside him. He gazes back at the camera, his head tilted slightly to the left, close to the first of five skulls that look like macabre extensions of his own body. The five skulls anchor the five living figures in the image and provide a figurative line of defense against possible threat. The Civil War was imagined as a white man’s war; visually devoid of black soldiers and their corporeal sacrifice, the imagery that remains is instead a visual register of white sacrifice. White soldiers dying for the sins of the country and the sins of black people—that is, the sin that is slavery. The photographic archive of the war is one of astounding substance and meaning, but also astounding absence and refusal. There, in the precise envisioning of the archive, we see few images of African Americans outside their prescribed roles of subservience; they are presented mostly as servants, refugees, contraband, gravediggers. We can imagine that the graves dug signify these men’s own buried or submerged citizenship that does not allow black Americans to firmly situate themselves within the geographic space of the nation. Instead, they are seen to be ever awaiting a future reconciliation that is never to arrive—but is always on its way.

John Reekie, A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1865. Courtesy of Getty Images.

These men form the boundary of a burial party for white soldiers as their bodies intimate a proximity to death that they negotiate alone. In this way, the fraught negotiation of national and familial cohesion is organized around a narrative reconciliation making them brothers or soldiers of the war, but only if they are white. Black Americans, as this image intimates, exist on the periphery of the national family, and documentary photographs illustrate this repeatedly. Further, these images tether blackness to death as legible, as destined and in proximate certainty.

Something of the memory of the American Civil War haunts the present, aided by documentary photographs. Beyond the six hundred thousand dead and the catastrophe of its ruined landscape, something else is present, palpable and visible. It is a hovering sense of national mourning that has not sustained African Americans within the national imaginary. “A scaffolding of bone we tread upon, forgetting,” according to poet Natasha Trethewey.15 A past and a future tense of racial hegemony. It begins in the photographic archive of dead Civil War soldiers, iconic images of stone-still battlefields littered with bodies that occupy the visual field, facilitating a process of mourning that reinforces citizenship and national belonging, yet black soldiers exist outside of this framework.

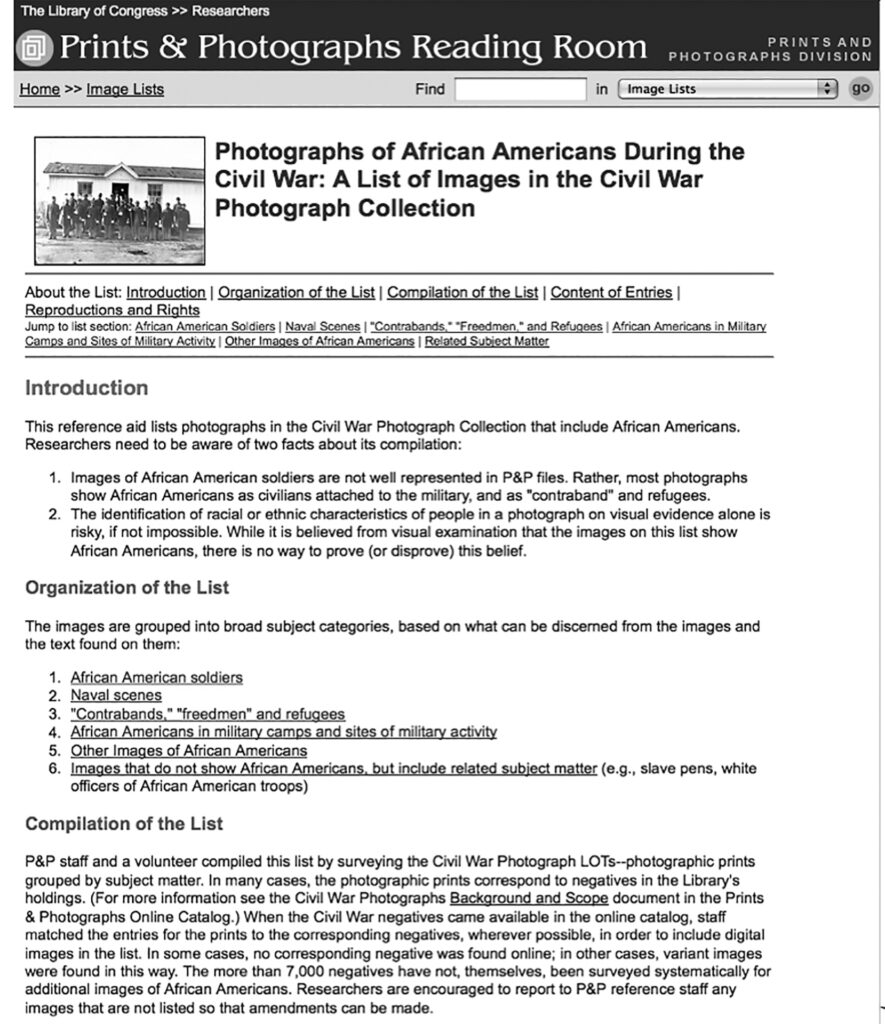

A perusal of the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress shows the available archive has its limitations. Before a search for African American soldiers in the Civil War can begin, the researcher is informed that “images of African American soldiers are not well-represented” in the archive. Instead, “most photographs show African Americans as civilians attached to the military, and as ‘contraband’ and refugees.”16 These images signal the visualization of a repeated metaphor of black subjectivity occupying an impossible duality of property and person, of contraband and comrade, and of refugee and citizen.

The paucity of images of African Americans in the photographic archive of the Civil War (composed of nearly one million images) replicates an erasure of visible blackness when that blackness is a part of the discourse of the event. In the aftermath of the Civil War and its ghostly remembrances, in the sliver of space between slavery’s demise and the spectacular production of lynching photography, the recovery mission of the nation doubled black death against a refusal of citizenship, necessitating the production of photographic memory on the part of African Americans to make space for the imagistic absence of black subjects and black subjectivity.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/, archived at https://perma.cc/NU8K-SXYK).

Of the famous Gardner photographs of deceased white Civil War soldiers blanketing battlefields across the country, Susan Sontag writes, “With our dead, there has always been a powerful interdiction against showing the naked face.” For Sontag, this is what gives the images their exceptional force, as “Union and Confederate soldiers lie on their backs, with the faces of some clearly visible.”17 It is a consolidation of racial alignment that allows this to be visualized and held in memory. White soldiers, even the traitorous Confederates, are seen as the epitome of sacrifice—to die for the preservation of an idea, white supremacy—while black soldiers register as the contraband white lives are sacrificed for.

Encased in a refusal to incorporate black people into the national imaginary, contemporary literature about the Civil War is more than just a reclaiming of the available archive: it is a reconfiguration of what it means to read against the grain of what is already there. I want to think about the photographic space opened by the onset of the Civil War as one that framed black subjectivity in increasingly narrowing parameters, even as a separate African American archive existed. I also want to think about the space of contemporary photography as expansive enough to imagine black futurity against the containing register of race and nation.

Decades after the Civil War ends, stereographs of black laborers culling cotton appeared in the United States. These images then, visually out of time, are also solidified through a photographic stasis that attempts to hold black Americans in a state of enslavement that seemingly never ends. The never-ending extension of slavery’s presence is the disciplinary framework of racialized violence we have come to know. How then to discuss the pleasures of looking when those doing the looking are white, while the wounded, exploited, and dead are black? Black writers, artists, and activists have not had the luxury of passive attention. Not when “photographs of dead black bodies surrounded by happy white onlookers” are a central feature of lynching images in the United States.18

Gathering Cotton on a Southern Plantation, Dallas, Texas, 1900. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The doubling mechanism of mortevivum is the schematic cartography of unbelonging that hinges on the absence of black bodies in the photographic archive of the American Civil War, and the hyperpresence of black bodies in images of the dead at the end of the twentieth century. Whiteness constructs the documentary photographic space within its own binary logic, marking the photograph in and through the bodies that it contains. If whiteness is sempervivum (the live forever) of the American Civil War in this documentary logic, then blackness functions as a default mortevivum (the death living).

In a comparative study of the United States and South Africa, Tiffany Willoughby-Herard writes, “The pursuit of whiteness leaves people less human, less capable of accountability for their own debasement, and yet thoroughly meritorious in their own view because by standard markers of socioeconomic status, they are successful.” Willoughby-Herard insists that “we begin to talk about whiteness as pathology, whiteness as diminished selfhood, whiteness as soul injury, and whiteness as death.”19 Whiteness as death. What spectacular production of death has whiteness, in its imperialist production, wrought? How might we consider how photography functions as an aid as well as a traitor to the mission of the propaganda of white supremacy? Soweto Riots utilizes shadows to illuminate that which cannot be gleaned without effort: the space of desire in the temporal iteration of blackness in its proximity to death. As I discuss in chapter 3 of Mortevivum, shadows and photographic practices align to promote an aesthetic of haunting that refers itself forward in time. If the empire is a shadow, its cloaking mechanism is also its ubiquity. Photographic terms oscillate between light and shadow, mutations of exposure and imagistic clarity. To this, South African apartheid adds its own enclosure—an archival world producing shadows for light and light for shadow.

Because racial empires are constructed around the idea of implemented order (i.e., white sovereignty) and the containment of a duplicating threat (black sovereignty), they exist to stifle the movement and will of those considered undesirable, recalcitrant, unassimilable. Photography is a necessary appendage of empire, and its racial dimensions are part of what allows it to have such a potent legacy. Archives of the colonial experiment in South Africa detail an aggressive campaign of disruption and bodily violence that has yet to be reckoned with in the public imagination. That specific set of decades—1948 to 1994—is its own imperial curation, and photographs dominate. So many images from the period have been reproduced so often as to be infamous in their ubiquity, like the United States in the nineteenth century and the 1950s and 1960s.

The Riff

Decades of removal, segregation, and racial violence converge in this image. It travels across temporalities. From the front page of the New York Times in 1963, it moved to every major city in the United States and multiple international news outlets, including Life Magazine. If it were described to you, its contours and graphic overtones relayed in words, you would recognize it sight unseen. The term iconic fails at the task of registering the total photographic symbolism of the civil rights movement era contained in the image. In Birmingham, Alabama, there is a monument based on Bill Hudson’s famous photograph of fifteen-year-old Walter Gadsden. It is a photograph of convergence. I think of Gadsden as one of the few members of black photographic production who is disallowed the basic tenets of privacy and whose relationship to this image remains a static force, holding him in time, over time, as an object of suffering.

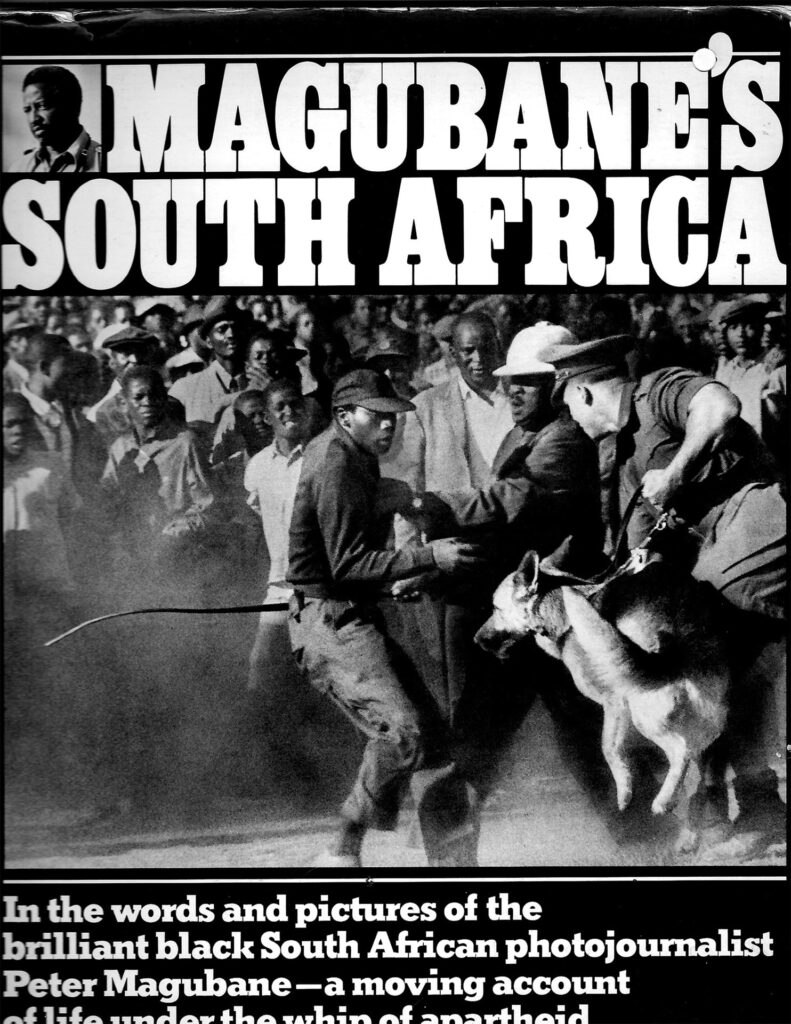

Four years after this photograph was taken, another emerged with similar visual constituencies. This one was taken at football game in Johannesburg, South Africa, and in it, another young man resists an imminent attack by a German shepherd. Both photographs traffic in what Martin A. Berger calls “sufficient signs of black inactivity and all white activity to read a reassuring narrative of race,” and as such, the images traverse national boundaries to reassert racial supremacy.20 Is it possible that Hudson’s photograph of Gadsden inspired the latter one by Magubane? Could it be that the infusion of German shepherds in South Africa directly results from photographs like Hudson’s from the United States? Magubane says in part about the photograph: “A policeman with a dog is a fearful thing. One of those dogs will rip you open. They never used dogs before but now they are common.”21 And so the question is, When exactly did it become common to use German shepherds in the facilitation of controlling black crowds in apartheid-era South Africa? What is the genealogy of this photographic phenomenon?

Bill Hudson, Police Dog Attack, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963.

In Bénédicte Boisseron’s Afro-Dog: Blackness and the Animal Question, Boisseron demarcates the fraught space between “canine aggression and black civil disobedience” that lingers as an aftereffect of slavery in the Americas and apartheid in South Africa. She writes, “What brings the dog, the slave, and the civil rights protester together under the same ‘ferocious’ stigma is their common claim to freedom, perceived ultimately as a feral claim.” Photographically, the presence of the German shepherd is often read as the chaotic disorder of black resistance. Boisseron continues: “The human and the dog compound each other’s constructed viciousness in a mutual ‘becoming against,’ the consequence of which is that the image of the vicious dog pursuing the slave has become a part of a collective consciousness that compulsively recreates—and each time reignites—the association of the vicious dog with truant blacks.”22 In a kind of visual fetish, viewers sublimate the desire for racial order onto the dog that ferociously represents the state, teeth locked onto flesh for the purpose of white supremacy.

Within and beyond a photographic history of exceptional aggression, black subjects negotiate space on gelatin silver prints alongside imminent or actual canine attacks. “It is just possible,” John Berger writes in About Looking, “that photography is the prophecy of a human memory yet to be socially and politically achieved. Such a memory would encompass any image of the past, however tragic, however guilty, within its own continuity.”23 This continuity is a neither/nor, both/and construction, moving geographically, historically, culturally, and linguistically across time. What if we attended to this construction for its antiblack contours to see what is already there?

Peter Magubane, Magubane’s South Africa.

To See What Is Already There

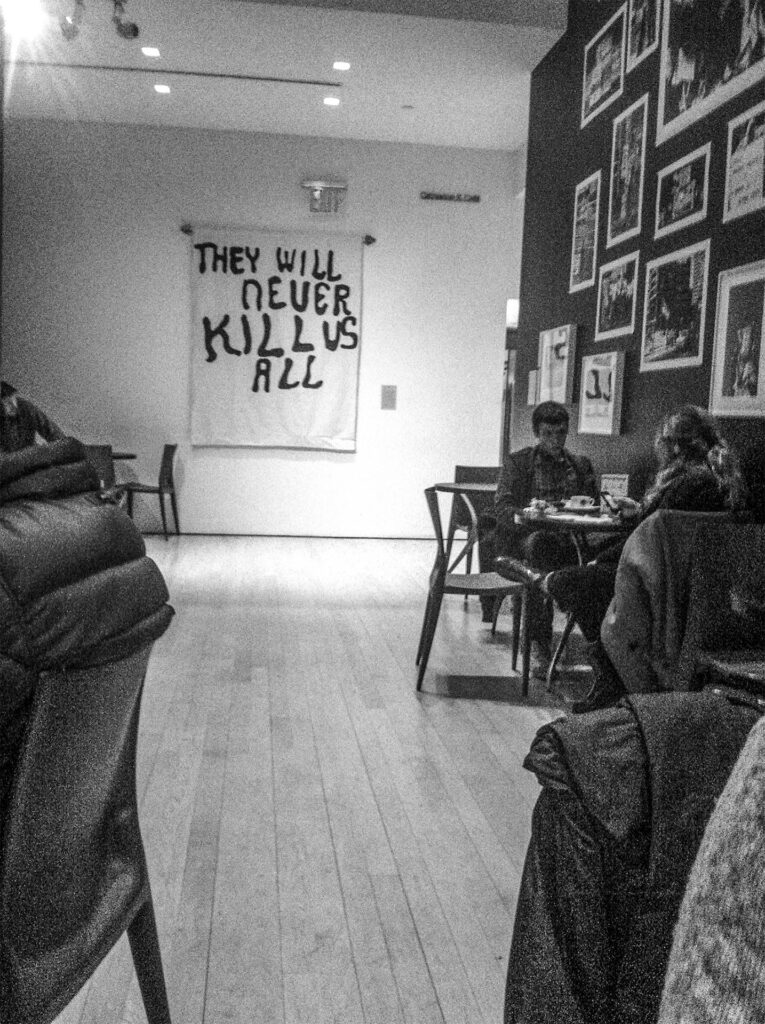

The 2012 exhibition at the International Center of Photography (ICP), Rise and Fall of Apartheid, depended heavily on the spectacular reproduction of black suffering.24 This it largely delivered, despite, I believe, its intent. Along with graphic images of black South Africans fighting against the regime of the racist state, there were interspersed images connotating the violence that, both unyielding and horrifying in its display, appears as a fixed event in the history of apartheid. Yet hung prominently in the ICP’s café area was a large white sheet with the words “They Will Never Kill Us All.” A future perfect statement (“they will never kill us all”) that is also a statistical threat to white supremacy (“never kill us”). But it is much more than this. While presenting the state’s ultimate goal (“kill”), the sheet is a response to what is a numerical impossibility (“kill us all”). As viewers circle their way around the exhibit on the first floor, the sign in the café is at the natural end of their journey. As they take in the totality of the exhibition and sit in the café enjoying a light snack or a coffee drink, the image appears to reinforce the perpetual nature of embattled states that attend black subjectivities. Presented with the casual effort one puts into placing a landscape painting on a hotel room wall, there is something compelling here but otherwise unremarkable, for the viewer to consider but not necessarily engage with. The landscape is a place the viewer never has to visit, unfixed and remote. It is an island where otherness lives. What could fix the gaze in this direction for more than the moment it takes one to read the line of text? That is a question for the archive, its silences and sounds, and the indifference that animates the viewer’s relationship to black subjects.

And so maybe a theory of photographic distrust is borne here—out of three centuries of the visual culture of racial hegemony. A space of black exceptionality combines Orlando Patterson’s articulation of “natal alienation” with Charles Mills and Saidiya Hartman’s delineation of the borders of black citizenship. In the symbolic register of the photographic imaginary, the empire still holds sway. Frantz Fanon writes: “This explosive population growth, those hysterical masses, those blank faces, those shapeless, obese bodies . . . these children who seem not to belong to anyone . . . all this forms part of the colonial vocabulary.”25 It also forms part of an imperial ocular expectation, trained and molded into melancholic terms. “The repetition of tragic southern African themes,” writes Paul Gilroy, is “deployed to contest and then seize the position of the victim.”26 What Saidiya Hartman refers to as the “slipperiness of empathy” within the structural resonance of American slavery has Gilroy’s version of postcolonial melancholia at its core.27 “In that slippage,” Christina Sharpe maintains, “is also the multiple ways that oppressive social systems—apartheid, ethnocentrism, and slavery—drive people in all places in the power structure ‘mad.’”28 In this “madness,” there are the unstated performative deployments of projected rage, poised and perfected for nearly two hundred photographic years.

A sign displayed in the café at the International Center of Photography during the 2012 Rise and Fall of Apartheid exhibition.

The visuality of this deployment is an ocularity that has its lens turned toward the proliferation of specific pained and nonliving bodies and the racial aftermath of indifference. In these moments of carnivorous voyeurism, we allow the image to culturally inform the very thing we see, regardless of the medium through which we see it. Photographs say, “I duplicate and extend your line of sight; you do the rest.” And we agree. “What the camera does,” John Berger argues, “and what the eye itself can never do, is fix the appearance of that event. It removes its appearance from the flow of appearances, and it preserves it, not perhaps forever but for as long as the film exists.”29 If we were to negotiate the terms of not perhaps forever, there would be a distinct racial dialogue that routinely places blackness outside the periphery of the temporal.

Archives of indifference permeate the photographic framework of black South Africa as subjectivity modulates racial visibility and civic transparency. Soweto Riots is a photograph of temporal conflation and elongation. An image of the witness, the voyeur, and the victim. A photograph of blurring visual constituencies: the figure, the subject, and the pawn. In the temporal demarcation of 1976, when this photograph was taken, we can also imagine the repetition of 1960 and 1994. “We thus live in an era,” Ariella Azoulay contends, “in which it’s difficult to conceive of one single human activity that does not use photography or at least provide an opportunity for it to be deployed in the past, present, or future.”30 The subjects in the photograph comport the management of the visual dissonance of a dead body in this image and enact past, present, and future in one frame. The past includes the American Civil War and the 1960 Sharpeville massacre; the present the US civil rights movement and the Soweto uprising; and the future anticipates the final death blow to the system of apartheid in South Africa in 1994.

There is a disturbing history of photographic violence attending black subjects, throughout the African diaspora and within the African continent. In the United States, these images conjure up a cartography of unbelonging, placing black bodies at the center of a sentient divide. From the space of the gaze, the viewer participates in what W. J. T. Mitchell calls the “ocular violence of racism,” by “observing” the photographic display of disjuncture.31 The viewer is present, therefore, not only to indict a voyeuristic participation in the violence and bloodshed of othered bodies, but also to engage the element of desire in the continual proliferation of a certain kind of black representation—a visual wailing cast in light and dark.

Magubane’s photograph also parses out articulations of gender that are not always present in the available archive. The veneer of safety within a category of unbelonging cannot sustain itself here. This absence of acknowledged inflictions of violence blankets the imagery involving black women. This photograph, framed by the two women standing closest to the body on the ground, marks this precise proximity (and its gendered pronouncement) as central to the composition of the image, as the two women are central to the framework of violence and removal, situated within this space of national violence.

Magubane’s image details the outward imperative of graphic death that, by this date in 1976, had become part and parcel of the haunting of colonial and postcolonial photographic practices. This is bodily injury under the accepted racial demarcation of expendable otherness. And the photographer framing the sight does so after state-imposed imprisonment, violations of his citizenship, and financial sanctions. “I had spent a total of 586 days in solitary, six months in ordinary jail, and five years as a ghost,” he writes in Magubane’s South Africa. “I had never been convicted of any crime.”32 Locating his professional isolation, juridical removal, and imprisonment within the elongated structure of subjective temporal shifts, Magubane marks time through the containing register of a silenced visual archive—his own.

Their Dead among Us

Death hovers and drifts over the photographic invisibility of black soldiers during the Civil War. Death frames the hideous decades of the reconstruction era and the spectacle of lynching that dominates the US imaginary thereafter. Photography posits black people in the United States as a default symbolic register. It explains a contemporary fascination with the digital proliferation of the imagery of black death. It details the particular national refusal to enclose African Americans within the safety of citizenship. It is the thing, according to Natasha Trethewey, “which must be accounted for.”33 It is the voyage nations obfuscate in order to continually refuse to regard. In the aftermath of the American Civil War, during the rise of American lynchings, Jacqueline Goldsby writes, “Lynching photographs figure the dead as signs of pure abjection, who radiate no thought, no speech, no action, no will; who, through their appearance in the picture’s field of vision, become invisible.”34 It is what philosopher Charles Mills refers to as “a dark ontology,” the process of seeing black subjectivity outside of the realm of fungibility, and it is something the nation is still grappling with.35

Buried in the earth in both marked and unmarked graves are the bodies of the 180,000 black Civil War soldiers who enlisted in the Union army during the war. Natasha Trethewey’s 2006 book of poetry Native Guard tells the story of one such African American soldier fighting for the Union. The Native Guard infantry regiment was based in Port Hudson, Louisiana, where formerly enslaved people and free men enlisted with the Union. The poem begins in 1862 (the year the regiment is reconfigured from the Confederacy to the Union) and ends the year the Civil War ends in 1865. The poem is an ode to the all-black regiment and its members’ pursuit of freedom and racial purpose. In the final stanza, the speaker reflects on the “things that must be accounted for,” a list of incomprehensible violence enacted upon those other victims of the American Civil War, African Americans:

1865

These are things which must be accounted for:

slaughter under the white flag of surrender—

black massacre at Fort Pillow; our new name,

the Corps d’Afrique—words that take the native

from our claim; mossbacks and freedmen—exiles

in their own homeland; the diseased, the maimed,

every lost limb, and what remains: phantom

ache, memory haunting an empty sleeve;

the hog-eaten at Gettysburg, unmarked

in their graves; all the dead letters, unanswered;

untold stories of those that time will render

mute. Beneath the battlefields, green again,

the dead molder—a scaffolding of bone

we tread upon, forgetting. Truth be told.36

Part of the useful availability of black bodies during the Civil War corresponds to their visual absence after the war ends. In producing Civil War monuments of the citizen-soldier, Kirk Savage asserts that the search was for an “American type.” And unsurprisingly, “what it meant for a face to be ‘American’ was not easy to define, but whiteness was a prerequisite—so obvious to most that it needed no comment.” As a consequence, “the figure of the black soldier, inextricably linked to the memory of slavery, became unrepresentable.”37 Trethewey’s poem “Native Guard” attends to the dead in a way that makes black presence available to the archive and representable. The poem functions as a found photograph layered with meaning and as a present commentary on the purposes of oral and written testimony. The speaker, using a pilfered notebook (taken from a Confederate homestead), marks down all that he sees like an image-maker assigned to collect documentary evidence. In the exhaustive extension of the black soldier’s body during the war, there is no unification, not even in death. The speaker produces this unification out of sheer force of will and history.

According to Karla F. C. Holloway, contemporary African American funereal practices developed from the segregated and exclusionary procedures of handling the dead during the latter half of the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century, and also from when black bodies during the Civil War were left “unclaimed,” stateless corpses belonging to no nation. In addition, she writes, “Black culture’s stories of death and dying were inextricably linked to the ways in which the nation experienced, perceived, and represented African America.”38 Mortevivum is the imagistic corollary to the production of insular white collectivity. The “our” that “our dead” intimates, and its concomitant exclusionary register, “their dead.” In this refusal to absorb black Americans into the constituency of the nation, they personify the very idea of removal as an impossible endeavor, nevertheless repeatedly attempted. Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric grapples with the juxtaposition of word against image as Rankine, a poet, grapples with the borders of the racialized body in the linguistic world. She writes: “Words work as release—well-oiled doors opening and closing between intention, gesture. A pulse in the neck, the shiftiness of the hands, an unconscious blink, the conversations you have with your eyes translate everything and nothing. What will be needed, what goes unfelt, unsaid—what has been duplicated, redacted here, redacted there, altered to hide or disguise—words encoding the bodies they cover. And despite everything the body remains.”39

The body and its remains blanket the Magubane photograph with diagonal constituencies as black subjectivity takes on the veil of witnessing, crowding out the divisibility of each of the figures in the photograph while also closing in on the borders of the photo and creating a more insular space. Through this mechanism, black South Africans are asked to prove a legibility of citizenship even as physical and metaphorical removal takes place. Within state-sanctioned violence and subjection, there is the desire for participatory engagement. “Here we see the first syntheses between massacre and bureaucracy,” writes Achille Mbembe in his essay “Necropolitics”—“that incarnation of Western rationality.”40 Magubane plays on the texture of this demarcation “between massacre and bureaucracy” playing itself out in the townships outside Johannesburg in the 1960s and 1970s. Life and death, movement and stillness, proximity and distance, shadows falling on earth—everything converges in this image. Clashes, actually, as it appears the photographed subjects mark this visual dissonance with the distance of their bodies away and apart from that of the decedent, but close enough to register the collective interiority of this loss.

The signification of transnational blackness in documentary form (prior to September 11, 2001) was one that invited a vision of corporeal obliteration, fetishized it photographically, and released the imagery as an ocular engagement recognizably compelling to a mass audience already racially immured. The viewer’s (Western, first-world, and white) projected investment extends the proliferation of the maimed (or contained) black-world subject, offering the viewer the ability to slaughter with the eye those who have been slaughtered out of time. This is what it means to live forever in the psychic photographic space of black peoples’ demise.

Thus, the South African scene from 1976 has the familiar afterlife of tyranny: the Sharpeville massacre in South Africa occurred in March 1960, soon after indigenous Africans resisted the mandates that stripped their state citizenship. This photograph, taken in 1976 during the onslaught of the Soweto uprising, refers back to 1960 and the unprovoked massacre that followed a series of rigid separatist policies now filed under the lexicon of a racist regime. By the time South Africa’s national experiment with apartheid came to an end in 1994, there was a temporal layering of contingent imagery that replicated this scene. The message is subtle, but clear: some people are supposed to die and do so repeatedly for the benefit (and citizenship) of others.

The Sharpeville massacre takes its name from the South African township bearing the burden of history on its shoulders. On what should have been a less than eventful day with a planned protest against the extension of the pass laws (requiring black men and women to carry a reference book with personal details contained within it), police opened fire on the group, killing sixty-nine and injuring hundreds more. If we think about the intersection of race, violence, and photography codifying black subjectivities within and beyond the corporeal framework, the role of the witness is of particular importance. The viewer (of, for instance, newspaper imagery) as an afterwitness yields to the on-site purveyor of the violence taking place—the people photographed alongside the maimed and the injured, their bodies providing the extended envisioning of projected desire. I want to think about the containment of space within these photographs as a solidification of racialized violence, violence that is part of the imagistic archive producing and extending the cartography of indifference. A violence that is as prevalent photographically as it is resistant to its own unpacking. This often marks temporal conflation as it is rendered here as pre-, post-, and neocolonial, inventing a lineage of similar imagery across disparate locations, framed to invoke the slippery nature of other people’s sovereignty. “In the colonial world,” Frantz Fanon laments, “the emotional sensitivity of the native is kept on the surface of his skin like an open sore.”41 This “open sore” is visually rendered as reproduced documented assaults against black flesh, and it is this sore that photography can reopen and infect. “Can you be black and look at this?,” the question that Elizabeth Alexander asks as she examines the ubiquitous violence of the Rodney King video, is present here as well.42 To be black and to look at this is to engage in the photographic dimensions of empire, to view the empire through the binary logic of sempervivum: white life and liberty rendered through black death and the constant invocation of unfreedom, of unbelonging. “Photography functions on a horizontal plane,” Ariella Azoulay writes. “It is present everywhere—actually or potentially.”43

Here, the earth holds information: bodies, lives, and the fictions of racial supremacy. We just have to look.

Lynching photography in the United States presents the witnessing of black death as an insular racial experience: white ease, pleasure, pride, and interest against black caution, anger, anxiety, and dread. At the same historical moment (the 1960s) that multiple African nations were gaining independence, South Africa’s experiment with apartheid was immortalized photographically through images much like Magubane’s. What is particular about this image is its early morning reckoning, its divided and multiple constituencies, its projection beyond time and through the impact of decades of displacement, marginalization, forced removal, murder, and indifference.

In layering the Civil War soldier and his duties with the black soldiers’ awareness of the permutations of the war event, Trethewey joins them together in a proximity to the dead. This proximity, often reproduced photographically, connects black labor to the dirges, the ditches, and the dangers of war participation, while also articulating their closer proximity to death by “those who still would have us slaves.” And so the enemy is everywhere—literally, for black soldiers, just as it is clear that danger and violence is everywhere for black people. White soldiers, who can cloak the visual markers of the Union or the Confederacy, are able, after the end of the war, to negotiate a difficult but possible reconciliation, which renders them as deserving of national respect and admiration. The speaker’s journal is another “page of history,” a palimpsest that troubles the negotiation of the past in the present:

April 1863

When men die, we eat their share of hardtack

trying not to recall their hollow sockets,

the worm-stitch of their cheeks.

Today we buried

the last of our dead from Pascagoula,

and those who died retreating to our ship—

white sailors in blue firing upon us

as if we were the enemy. I’d thought

the fighting over, then watched a man fall

beside me, knees-first as in prayer, then

another, his arms outstretched as if borne

upon the cross. Smoke that rose from each gun

seemed a soul departing. The Colonel said:

an unfortunate incident; said:

their names shall deck the page of history.44

“Native Guard” attends to the dead in a way that makes black presence available to the archive—a found photograph filled with meaning. “Some men shall deck the page of history / as it is written on stone. Some will not.” The speaker, using a pilfered notebook (taken from a Confederate homestead) marks down all that he sees like an image-maker assigned to collect documentary evidence.

June 1863

Some names shall deck the page of history

as it is written on stone. Some will not.

Yesterday, word came of colored troops, dead

on the battlefield at Port Hudson; how

General Banks was heard to say I have

no dead there, and left them, unclaimed. Last night,

I dreamt their eyes still open—dim, clouded

as the eyes of fish washed ashore, yet fixed—

staring back at me. Still, more come today

eager to enlist. Their bodies—haggard

faces, gaunt limbs—bring news of the mainland.

Starved, they suffer like our prisoners. Dying,

they plead for what we do not have to give.

Death makes equals of us all: a fair master.45

Replicating the violence of the gaze, the “fixed” eyes “staring back,” the speaker is haunted by dreams of open eyes that have the capacity to see beyond death to the refusal of the consideration given soldiers who are white. Moreover, death’s equality even extends to the color of the skin. With white bodies turning black after death, Drew Gilpin Faust writes, “Soldiers looked with horror upon bodies that seemed to change color as they rotted, commenting frequently upon a transformation that must have borne considerable significance in a society and a war in which race and skin color were of definitive importance.”46 Here, the earth holds information: bodies, lives, and the fictions of racial supremacy. We just have to look.

Forever, Contained

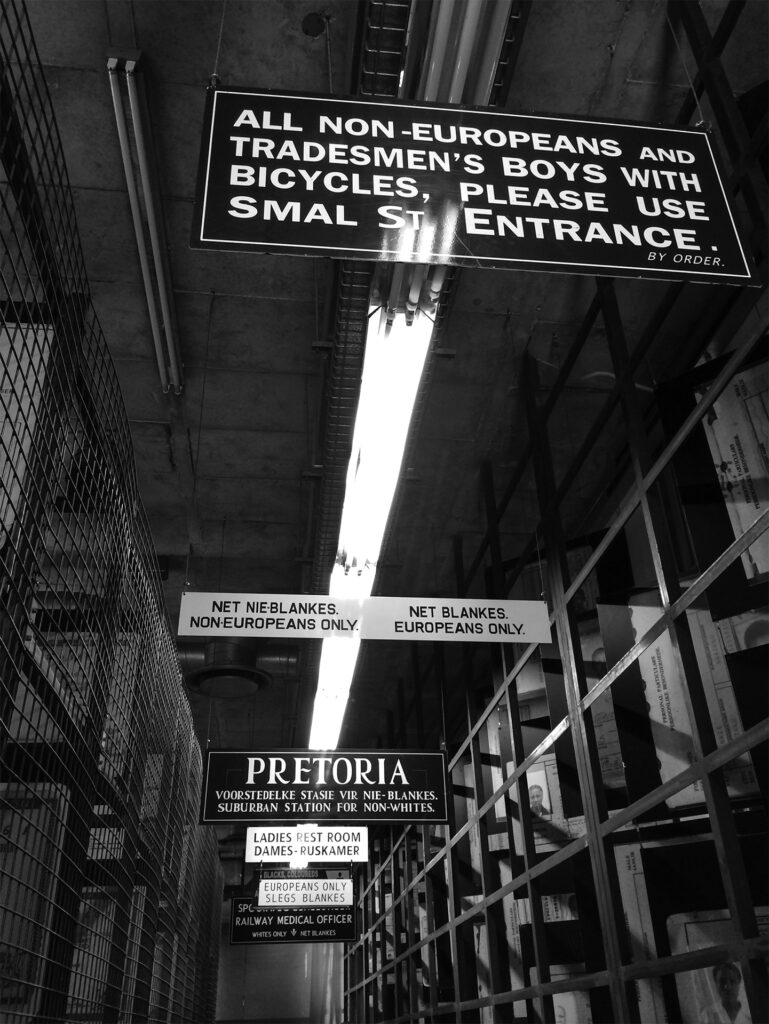

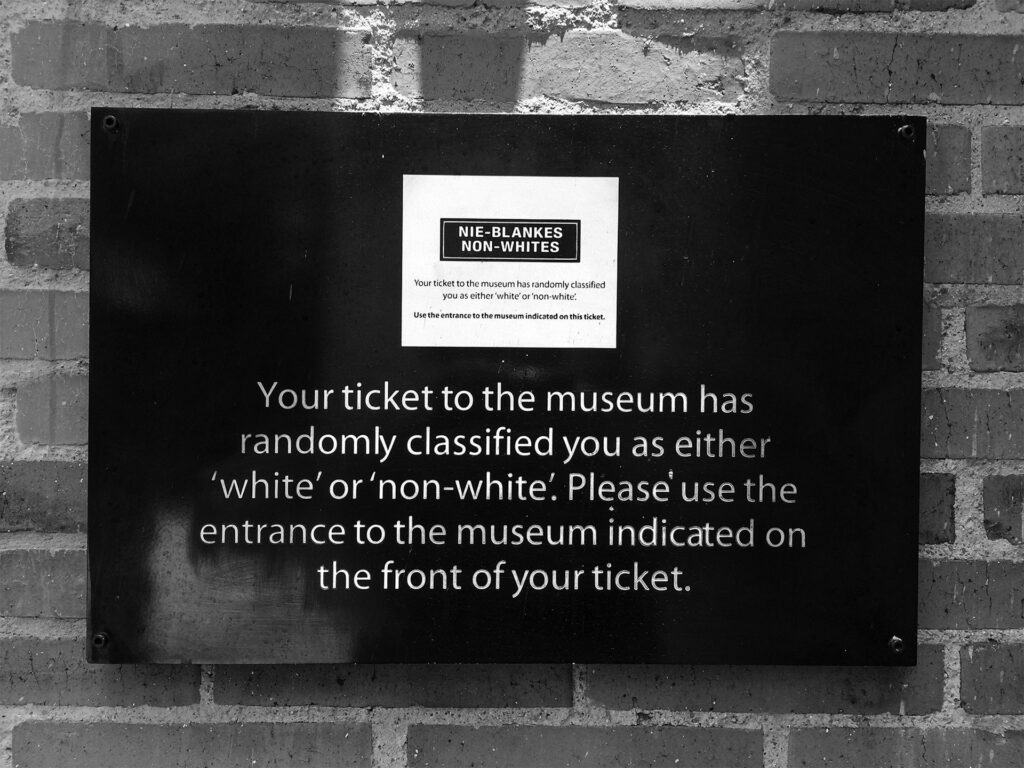

Opening in 2001, South Africa’s Apartheid Museum is the first of its kind, a live forever of a different sort. Located in Johannesburg, the museum’s ambitious design is meant to signal the better future of a postapartheid world. Inside the structure, visitors are meant to experience the racial stratification of the regime as soon as they enter the museum. Admission cards produce a binary of “white” and “nonwhite” identity in order to critique apartheid’s classification system. “Your ticket to the museum has randomly classified you as either ‘white’ or ‘nonwhite,’” the ticket holder is informed. They are then instructed to “use the entrance to the museum” in accordance with the ticket classification. This binary logic separates the entrances, and so visitors immediately perform privilege or racial subjugation based on the statistical whimsy of an entrance card. The second person allows for a familiar intimacy to float just above the surface and hover close at hand. With an uncanny ability to reinforce the very hierarchy it purports to deconstruct, white visitors, in a ubiquitous consolidation, may have their whiteness reified by an experiment in memory making that rhetorically orders what was initially a juridical practice. In 2001, seven years after the end of the apartheid regime, a museum opened to relegate the system to the past. It is still participating in this endeavor.

Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa. Photograph by the author.

The temporal framework of apartheid gives the second half of the twentieth century a precise visual location through which to process the photography of antiblackness projected against a world stage. For nearly fifty years, documentary photographs punctuated media coverage of the violence apartheid engendered; from forced removals in places like Sophiatown (Kofifi) to the stripping away of citizenship rights for black South Africans, Afrikaans being chosen as the official language in schools, the renaming of geographies from indigenous African names to Dutch/European names, and ceaseless murders, beatings, and arrests. It is a precise marking that troubles the discourses embedded within—namely, histories of empire, African studies, visual culture studies, black studies, and gender studies. It is to trouble what Tina Campt calls the “lower frequencies of transfiguration enacted at the level of the quotidian, in the everyday traffic of black folks with objects that are both mundane and special: photographs.”47

Documentary photographs manage the fissures of citizenship that clamor for visibility in the modern era. Carrying the memory of black South African death imagistically, coverage of apartheid’s slow but eventual demise enfolds the dead in a blanket of racial tension that unravels without care. The viewer is central to this unfolding, as an assumed investment structures the order of how much viewers are willing to absorb. Somewhere between collusion and implied consent, a viewership adapts to the implicit needs of antiblackness. Compartmentalized photographs appearing in the media negotiate a binary between legitimate death and illegitimate life. The former allows the visual space for predetermined incommensurability; the latter is an example of surfeit populations eligible for culling.

Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa. Photograph by the author.

Photographs crowd the interior of the Apartheid Museum with spatial intimacy, then spread outward like propaganda. The physical enclosure of the museum connotes the binary production of a worldview structured as black and white (even as the racial category of “colored” also exists). Even the nuances mark a precise territory. How, then, are viewers to navigate a haunted space of racialized trauma while attending to the difficult work of apartheid’s antiblack violence? What ways of measuring cognitive recognition are available to the viewer? And how has the history of photography in South Africa produced an archive of imperial practice barely fifty years into its modern existence? Part of this project concerns the iterations of belonging that reinforce the space whiteness occupies as it constructs modernity as a pale mission of purposeful invasion. Empires engage photography for its disciplinary mechanisms, what Susan Sontag calls “collective instruction.”48

Hans Haacke, Voici Alcan, exhibition at Galerie France Morin, Montreal, 1983. Courtesy of MIT Libraries.

In the popular imaginary concerning this temporal overlay, photographic images solidify the stark binary logic placing black South Africans outside the orientation of self-possession, of sovereignty. In 1983 the Galerie France Morin in Montreal featured an art piece by Hans Haacke with a postmortem photograph of black South African political activist Steve Biko. Biko’s dead body is the center image in a triptych, and is bracketed by images of living, vibrant stage performers from the Montreal Opera. They are as alive in the photographs as Biko is dead on a coroner’s table. “Even though Voici Alcan was made for an exhibition in Quebec,” Haacke states in an interview, “the Tate Gallery audience in London could relate to it, particularly because, due to the historical and close trade relations between the U.K. and South Africa, apartheid is a hot topic in London.”49 Audiences in London could also relate to the image because the dead body of Steve Biko is presented as the central image, reinforcing a hierarchy of life and death that is racially bound. Although certainly a protest image, Voici Alcan also visually reproduces the violence it seeks to indict. In order to highlight the constancy of black death against its binary variable of white life, documentary images (even when in art productions) offer black suffering as a way to understand the aftermath of empire.

The Aftermath of Empire

James Q. Whitman’s Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law draws out the historical connection between racist Nazi policies and racial segregation in the United States: “In the early twentieth century the United States was not just a country with racism. It was the leading racist jurisdiction—so much so that even Nazi Germany looked to America for inspiration.” Whitman continues:

In the early twentieth century the United States, with its deeply rooted white supremacy and its vibrant and innovative legal culture, was the country at the forefront of the creation of racist law. That is how the Nazis saw matters, and they were not the only ones. The same was true in Brazil, just as it was true in Australia and South Africa, just as it was true of the German colonial administrators who went hunting for a model for the making of anti-miscegenation law. And while the Nazis liked to mention South Africa as a fellow traveler, in practice they found very little South African law to cite in the early 1930s. Their overwhelming interest was in the “classic example,” the United States of America.50

Although there is a vibrant national policy of self-congratulation as it concerns America’s racist past (and how the country managed to “overcome” it), many of the images from the US civil rights movement are simply repetitions of corporeal violence against African Americans. They illustrate the peculiar lens through which viewers were galvanized to bring about change while also cementing the idea of perpetual black suffering. Leigh Raiford uses the term critical black memory to encapsulate the surfeit of imagery that must be held in tandem with black narratives. “Black memory,” she writes, “also describes and carries within it the failures of the past: the failure to produce the desired political transformations, the failure to create or sustain a culture of mourning or to successfully work through that mourning. . . . Black memory has also been a burden, turning experiences into icons, forcing racial and gender conformity and eliciting prescribed responses to racial events.”51 Some of those responses can be found in the viewer’s expectations that conform to perceptions of the lack of agency on the part of black subjects.

Thinking through an imperialist lens as it relates to antiblackness requires a spatial analysis that takes the global seriously. Lisa Lowe’s The Intimacies of Four Continents tracks goods, people, and racial concepts as they move across geographies and inform the way modernity comes into being. If you are paying attention to the archive, she writes, “one notes explicit descriptions and enumerations, as well as the rhetorical peculiarities of the documents, the places where particular figures, tropes, or circumlocutions are repeated to cover gaps or tensions.”52 One also notes that these “gaps” and “tensions” play themselves out photographically soon after the invention of the medium, which corresponds to the mandates of the end of the industrial age, or the “age of mechanical reproduction” that Walter Benjamin examined nearly one year after the invention of photography.

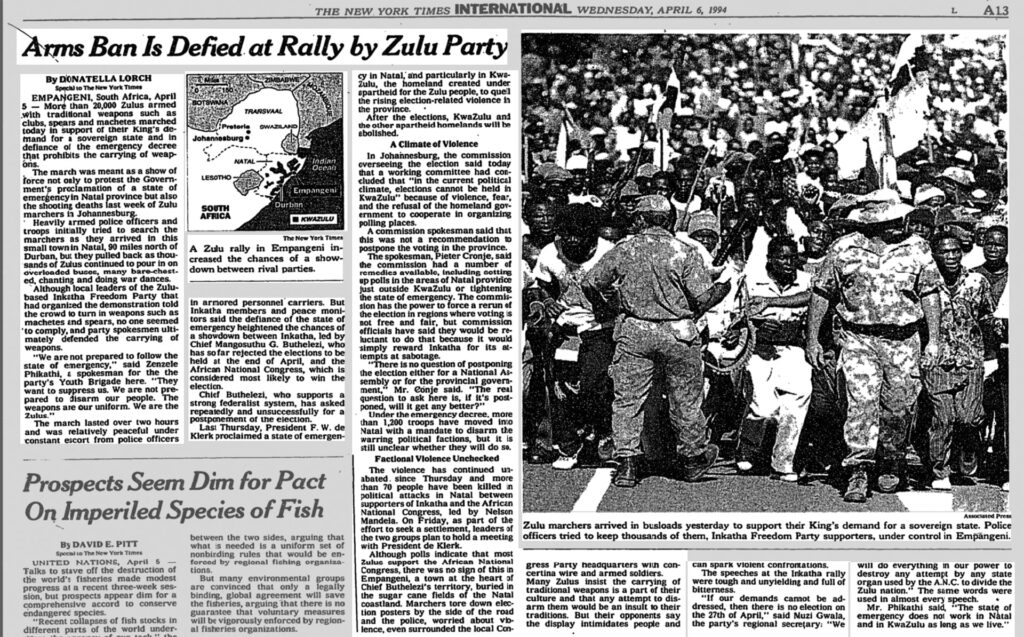

The viewer has much to manage: where to center the eye, hold the gaze . . . what to keep, disregard, and deeply notice. In a photograph published in the New York Times in April 1994 (figure 1.14), Zulu protesters march in support of “their King’s demand for a sovereign state.” The image shows a group of people moving forward, front-flanked by two police officers. Bodies fill the frame of the photograph, giving the viewer the sense of a claustrophobic crowding that moves beyond the frame itself. It is possible to read this image as the culminating metaphor for the propulsion of black South African agency, but I suspect this was not the reason the image was chosen. With no singular figure for the viewer to hold in visual harmony unobscured (unlike the May 1, 1994, front-page image of Nelson Mandela, the default center moves ever so slightly to the right. There, one of the two officers, head turned to the left, occupies visual space. If the forward progression (political, juridical) of a new South Africa is to be documented in the media, outlets like the New York Times will only do so if the subtle (or graphic) metaphor of white guidance against black sovereignty can be rendered visually. Nevertheless, by 1994, South Africa existed within the structures of the photographic imaginary as the symbolic register of this work of both extermination and settlement. In the latter half of the year, the “new” nation being reformulated considered what it might mean for a white minority to be on the margins of the visible sphere of political power. Conversations about the reconfiguration of the national flag, the falling of monuments, and the renaming of streets and bridges filled the op-ed pages of newspapers like the New York Times. Photographs were disinvested of previous racial tensions and words replaced imagery. But even this has a past and a present tense.

Interior page of the New York Times, April 6, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International.

Future Tense

Documentary photographs occupy symbolic and literal space in the Apartheid Museum. It is a space that negotiates the concept of empire through a hierarchy of the visual that reinforces the protective comfort of white supremacy. Like many other spaces of representation involving black subjects, this one emphasizes white comfort while demonstrating the far-reaching capacities of black pain. If the empire is an eye, then it is one part sight and one part blindness, for it moves between these two spheres of visibility. Data collecting, surveillance, and the production of propaganda materials frame imperial directives. For a large swath of photographic history, imperial constructions dictate the manner and mode of exchange. “All photographs are, to some extent, souvenirs,” Zahid Chaudhary writes, “insofar as they give shape and signification in the midst of the uncertainty of the present at the moment the aperture is set to work, and the resulting photograph invokes the distance from the past, which is now handed down as a framed scene in the midst of the disappearing present’s uncertainty.”53 Apartheid, as a particularly photographic regime, swiftly recycles imperial imagery in place in other national contexts so that the fullest measure of hierarchical structure is sustained.

The shadow of the empire is indigenous to the photograph, and so is its undoing. Life, death, and everything in between exist here. The solemn May 1, 1994, photograph of Mandela has a counterpart in the image of the newly elected president displayed on the newspaper’s front cover on May 3. Francis Cline’s piece “A Joy Born in Pain Dances in the Street” features a smiling Mandela, mid-dance, claiming victory in the historic presidential election. This time his image is to the right of the middle of the front page, as a photograph of buoyant celebrants react to the final vote tally for the next leader of South Africa. The top image takes some time to parse out—multiple people and their exuberant expressions/bodily gestures converge in the photograph to illustrate what is referenced by Mandela’s centralized image. There is movement in both images, and one can read in this movement the forward progress resisted by a recalcitrant white supremacist regime, or the end result of continued black agitation. Either way, the photographs are informative in their ability to offer ways through and around apartheid without disturbing the haunting presence of white supremacy. The question then remains, What is to come after apartheid? Perhaps the answer lies in what has already been allowed to exist.

Documentary photographs grapple with the effect/affect dualism that navigates the parameters of visible and intangible subjectivities. Some of the choices made by editors and newspaper staff are practical and accidental. Some are not. But documentary photographs allow a space to explore the often binary opposition of black and white (of photographs and people). Often, particularly within the space of a daily international newspaper, words are set against imagery, and black subjectivities are strewn about, devoid of the attention to detail that would reinforce their humanity. “A general imperial right to seize and take was practiced as given and unlimited,” Ariella Azoulay writes. “The use of the camera was built on this right to take—to take photographs in worlds that were ‘opened up’ for them by imperial agents who socialized them to see this right as inalienable, given to them for the sake of humanity, and could be exercised regardless of the will of those depicted as paradigmatic victims of imperial violence.”54 The photographic conundrum of apartheid, with its signposts and signals, is symbolically disappeared through the hard-won “success” of Mandela’s election and the “joy dances in the street” visually held together on the front page of the New York Times. This is the through line: There is no need to look back. Only forward. And only forward can all of the violence, dispossession, and bloodshed be resolved. Much like South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the motto of which was Healing Our Past, this is a reverse trajectory, suturing the past with the present but focused intently on the future. Mandela’s inauguration speech announced in part: “The time for the healing of the wounds has come. The moment to bridge the chasms that divide us has come. The time to build is upon us.”55 And indeed, this is what the photographs imply. From healing wounds to bridging chasms, the visual rhetoric presented in popular media mutes the force of the apartheid regime in order to refuse the need to examine the past.

Front page of the New York Times, May 3, 1994. Courtesy of PARS International.

The empire is an archive of photographs rendered in the service of a separatist state. The United States’ Jim Crow era of racial segregation doubled as the imagistic referent of a scopic regime, and one meant to surveil and impose its mandates on black subjects violently. It was also meant to solidify the hierarchy of white over black in the psyche of southern citizens navigating a post–Civil War America. That South Africa’s apartheid regime took hold in the 1950s just as the United States was witnessing the demise of racial segregation in the South is not accidental. If we consider the work of observation, duplication, and data collecting done by white South Africans in the decades after de jure segregation began in the US South, we know that photography and its ability to quickly render the impossible binary of racial demarcation via a visual apparatus was central to this experiment.

Two women stand near the left of the center of the frame of the photograph. And they orient the eye of the viewer. The center contains no body. But there is a body on the ground. Someone no longer alive, but occupying space. One body, its photographic archive, and the transnational empire left lingering in its wake. This is a photograph of shadows on ground, of the singular mandates and imperatives that find their way into an image whether the viewer sees a body, a subject, a figure, an empire, or the faint outline of the imprint of loss.

The empire is a shadow, marked by figures both there (visible) and not there (invisible). Black suffering, rendered photographically, keeps the shadow in play and the center of subjectivity off to the side where it can be both seen and disregarded. If antiblackness is the weather, as Christina Sharpe writes, if it “necessitates changeability and improvisation,” then photography is how the “weather” registers visually to others.56 And photography is the mode and the medium of that register. Weather must be survivable. Bearable. Possible to evade when necessary. In short, weather must be able to be weathered, and there is little of the history of photography that offers this to the viewer. Not because these images are not present, not available, but because they are not allowed to usurp the force of white supremacy in the desire of viewers to disregard black agency upon seeing black subjects in the frame. And that has everything to do with the ubiquitous force of antiblackness in the very air we breathe.

Apartheid Museum entrance sign. Photograph by the author.

Note 3

Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2001), 35.

Note 4

Achille Mbembe, Critique of Black Reason (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 55.

Note 5

“Voyage through death,” Robert Hayden writes. “Voyage whose chartings are unlove.” Hayden, “Middle Passage,” in Collected Poems (New York: Liveright Publishing, 1985), https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43076/middle-passage, archived at https://perma.cc/WF53-8C5U.

Note 6

White life set against default black death functions much in the same way as the rhetoric around freedom is structured through the concept of unfreedom, which black subjects, enslaved or free, occupy.

Note 7

Quoted in “Living Memory: A Meeting with Toni Morrison,” in Small Acts: Thoughts on the Politics of Black Cultures, Paul Gilroy (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1993), 178.

Note 8

Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “empire, n.,” accessed August 28, 2018, http://www.oed.com, archived at https://perma.cc/Z6XC-694P.

Note 10

Peter Magubane, Soweto Riots, South Africa, 1976. International Center of Photography.

Note 11

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998).

Note 12

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Note 13

Ken Gonzales-Day, Lynching in the West: 1850–1935 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 88.

Note 14

Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 127.

Note 15

Natasha Trethewey, Native Guard: Poems (Boston: Mariner Books, 2006), 30. “Native Guard” is a suite of ten poems about the military regiment.

Note 16

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division (https://www.loc.gov/pictures/, archived at https://perma.cc/NU8K-SXYK).

Note 18

Toni Morrison, The Origin of Others (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 59.

Note 19

Tiffany Willoughby-Herard, Waste of a White Skin: The Carnegie Corporation and the Racial Logic of White Vulnerability (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 95.

Note 20

Martin A. Berger, Seeing through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

Note 22

Bénédicte Boisseron, Afro-Dog: Blackness and the Animal Question (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 39, 51, 76.

Note 24

The subtitle of the exhibition, Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, gives some context to the day-to-day oppressions the apartheid regime imposed, which were meted out in images meant to reinforce the power of white supremacy on black subjects (see https://www.icp.org/exhibitions/rise-and-fall-of-apartheid, archived at https://perma.cc/8H6K-TURQ).

Note 26

Paul Gilroy, Postcolonial Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 105.

Note 27

Hartman discusses the abolitionists’ attempt to utilize the discourse of empathy in order to reify their centrality as the figure of investment. “The difficulty and slipperiness of empathy” is that the one who is the intended focus of this empathy gets lost in the gesture. She writes, “Properly speaking, empathy is a projection of oneself into another in order to better understand the other.” Further, she asks: “Can the white witness of the spectacle of suffering affirm the materiality of black sentience only by feeling for himself?” Hartman, Scenes of Subjection, 18–19.

Note 28

Christina Sharpe, Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 87.

Note 34

Jacqueline Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 231.

Note 35

Charles Mills, Blackness Visible: Essays on Philosophy and Race (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998), 70.

Note 37

Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 162, 167.

Note 38

Karla F. C. Holloway, Passed On: African American Mourning Stories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 6.

Note 46

Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Vintage Press, 2008), 57.

Note 49

Yve-Alain Bois, Douglas Crimp, and Rosalind Krauss, “A Conversation with Hans Haacke,” October 30 (Autumn 1984): 23–48.

Note 50

James Q. Whitman, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), 138.

Note 51

Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 62–63.

Note 52

Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 35.

Note 53

Zahid Chaudhary, Afterimage of Empire: Photography in Nineteenth-Century India (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 64.

Note 55

Nelson Mandela’s inauguration speech, May 10, 1994; see https://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/read-nelson-mandelas-inauguration-speech-president-sa, archived at https://perma.cc/P767-E27X.

Note 56

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 106.