Introduction

This is how you make a gelatin silver print: the negative is placed in a photo enlarger, its duplication immersed in chemicals as precise as the movement of time. Silver salts (chlorine, bromide) sustain the emulsion that propels the visualization of the print. It is a living thing. It is a dead offering (or, in the words of Roland Barthes, “it is the living image of a dead thing”).1 And yet, “on top of brown-gray paper,” Michael S. Harper writes, “human images rise.”2 Human images in photographic reproductions are sights that compel others to look. Whether this action is to regard with intention or disregard with indifference, looking is a disciplinary and disciplining act3—one that nearly two hundred years of photographic history has inculcated into the naturalization of specific investment. And antiblackness blankets this history like a cloak with no beginning and no end, offering only momentary exercises of reprieve. And almost never on purpose.

Analog photography, what Beaumont Newhall referred to as “the mirror with a memory,” established itself by the late nineteenth century as a force with which to contend. Between its documentary and artistic pursuits, the genre was also central to the burgeoning eugenics movement in the United States and Great Britain. Along with the spectacular technological achievement that is photography, there is, almost immediately, what John Tagg refers to as its “disciplinary frame.”4 For black subjects, this disciplining, its surveillance and containments, necessitates an ocular vigilance that is difficult to sustain. There are others in the frame, visible or not. These others register in ways that set black subjectivity into disarray. They are the assumed inheritors of a right to their humanity that is not assumed for others.

It is a ghostly apparatus, photographic production, and it always has been. “Photography is a kind of primitive theater,” Roland Barthes contends. “A kind of Tableau Vivant, a figuration of the motionless and made-up face beneath which we see the dead.”5 When photography and antiblackness are conjoined, black people become the dead that we see. This means that in the generality of a visual imagination that looms large and contains “multitudes,” black subjects routinely receive short shrift.6 In as many ways as black diasporic subjects are presented as bodies of use, photographic accompaniment is regulatory, inflexible, and graphic in its production. To be seen in this environment is to be exposed to the violence of the gaze, particularly when it appears as an objective documentary photograph simply detailing what has already taken place.7

When photography and antiblackness are conjoined, black people become the dead that we see.

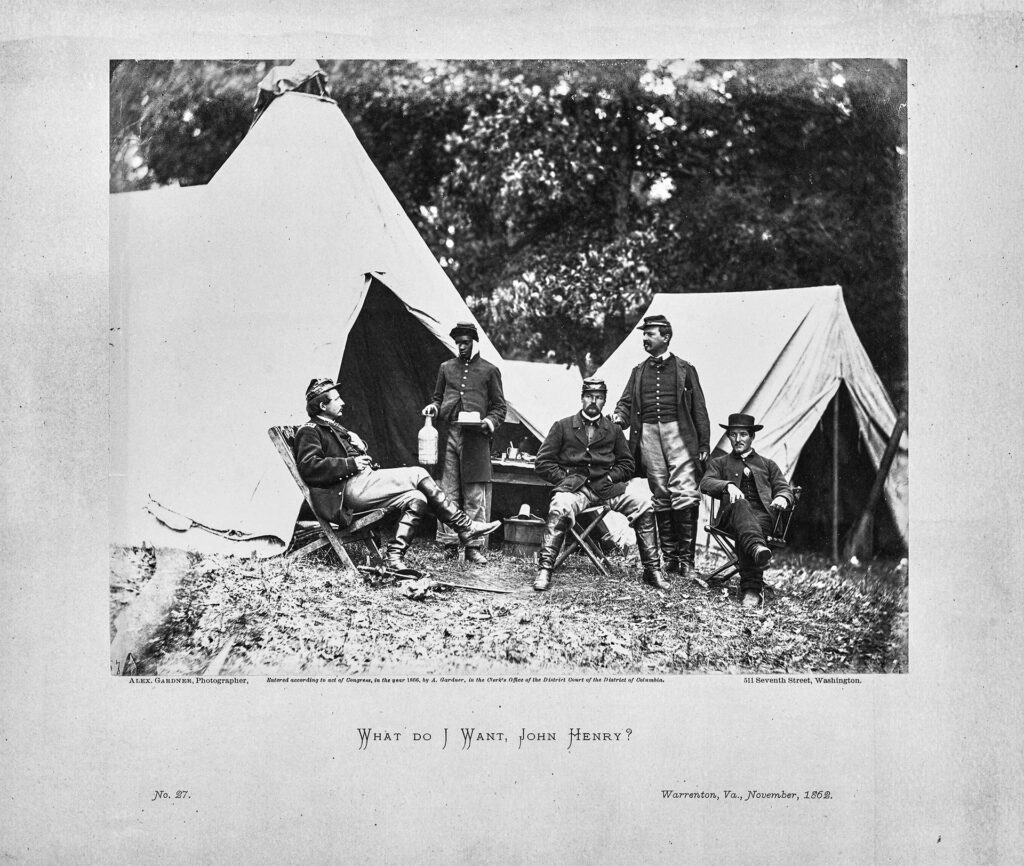

These photographs are instructive for what they can tell us about the intersection of race and the visual. In images from the American Civil War, for instance, we see the careful curation of a racial hierarchy that is also gendered male. We see the narrowed roles that African Americans are relegated to occupying and the violent intimacies they must abide to survive. The extended narrative accompanying the photograph confirms the refused access to citizenship that black American soldiers in the Civil War experienced. This erasure looms large in the images and text in Alexander Gardner’s 1866 work, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. About the photograph of an African American soldier photographed serving his military “masters,” the text reads: “Although his head resembled an egg, set up at an angle of forty-five degrees, small end on top, yet his moral and intellectual requirements were by no means common. His appreciation of Bible history was shown on many occasions. For instance, he always considered Moses the most remarkable of quartermasters, in that he crossed the Red Sea without pontoons, and conducted the children of Israel forty years through the desert without a wagon trail.”8 The narrative’s fixation on John Henry, the only black person represented in the image, is meant to demean in image what is “elevated” in text. An entire photographic universe unfolds along these lines.9

Alexander Gardner, What Do I Want, John Henry?, Warrenton, Virginia, November 1862. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Living in the tangible autonomy of existence that is then curtailed by the photographic frame, black subjects breathe life into representation by merely being present in front of other people’s eyes. “Because, like all other institutions and practices,” artist Michèle Pearson Clarke writes, “photography’s history reveals a gross complicity with white supremacy, and its emergence during the nineteenth century meant that it was immediately and specifically pressed into colonialist service.”10 Gardner’s book is the exploration of photography “pressed into colonialist service” that defines the contours of antiblackness visualized. Clarke continues, “Photography, then, did not so much record the reality of Blackness as signify and construct a way of seeing it.”11 To “signify and construct” is the great power repeatedly deployed then disavowed when photography and antiblackness converge. Performing the structural racism it embodies, the viewer’s indifference is ultimately the most telling. Measured quantitatively, a viewing audience predisposed to accept the tenets of white supremacy will have little in the way of expansive engagement when presented with black subjects in a photographic print. There is a temporal collapse when blackness and photography converge, which threatens to flatten the interaction. This flattening is a direct consequence of the lack of care proscribed to black subjects within documentary photography in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Prominent African Americans from Frederick Douglass to W. E. B. Du Bois worked tirelessly in the early decades of photography’s emergence to illuminate the inner lives of black Americans through the medium that was referred to as “painting with light.”12

An entire photographic universe unfolds along these lines.

For Du Bois in particular, his curation of portraits for the 1900 Paris Exposition is one important example. “Black photographers,” Deborah Willis writes, “whose work Du Bois drew on for the Paris Exposition, offered a provocative challenge to the blatantly stereotypical images of African Americans as inferior, unattractive, and unintelligent. Their photographs served as evidence that black Americans were as multifaceted as anyone else, and they played a key role in making the black experience visible.”13 Beyond visibility, there was an essential mandate that viewers invest in the aesthetic production of black subjects. In this way, they could be visually retrieved with their humanity fully intact. However, photography’s history (and by extension photography studies) is a catalog of othering, surveillance, and the violence of objectification. Bongani Madondo argues that “photography, on its own, is a technological response to the tableaux of its surroundings . . . it is history’s roving third eye.”14 Mortevivum explores this “third eye” as it exists on the cusp of the twenty-first century, where it seems work is still to be done to render black lives legible outside destruction.

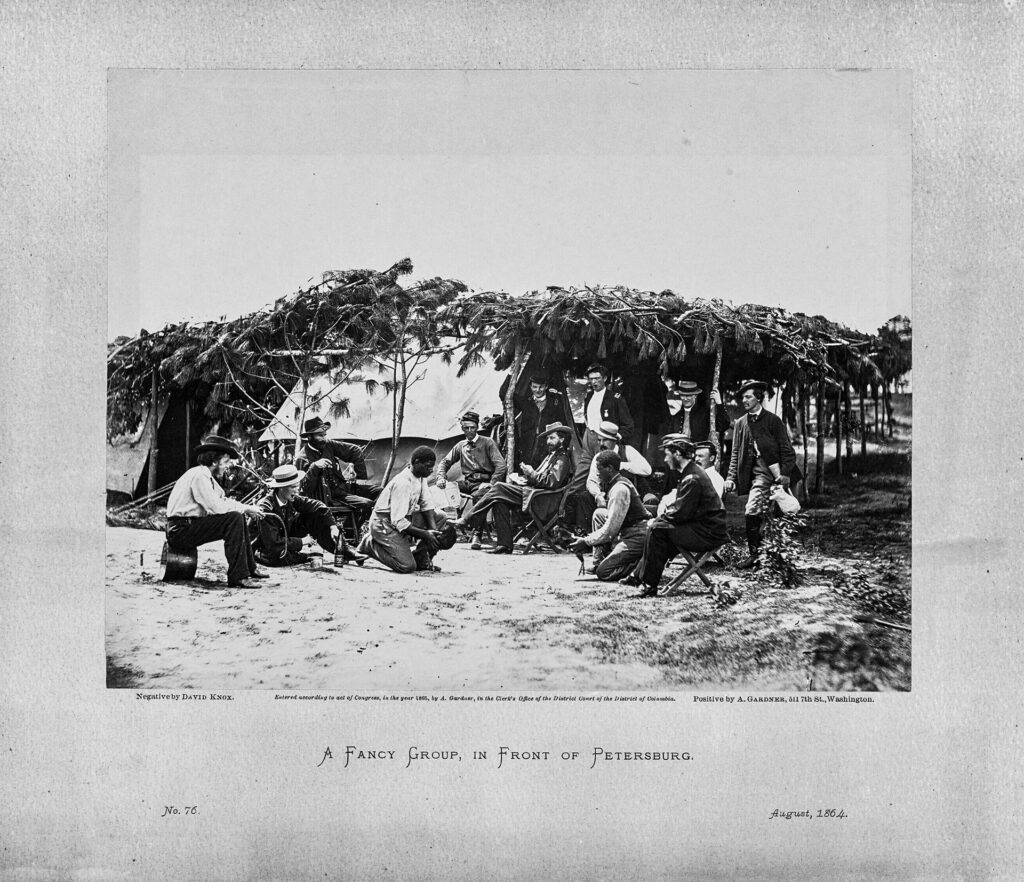

The destruction is the point. Its aims are imagistic and corporeal, representational and juridical. In its aggregate form, antiblackness sutures the line between active and passive racist participation. It requires very little to keep itself going, having relied for so long on the violent foundation it was built upon. “Narrative temporality,” Lisa Lowe reminds us, “is itself a powerful vehicle of liberal progress, as evidenced in the emplotment of slave emancipation, in which the slave subject develops in time, constituting a story of an enslaved past that culminates in freedom achieved in the present.”15 The Gardner photograph in figure 0.2 is an example of this narrative temporality, one which would shape viewers’ perceptions of black belonging in a national framework after the end of the American Civil War.

Alexander Gardner, A Fancy Group, in Front of Petersburg, August 1864. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Two young black men facilitate a cockfight for the pleasure of the white soldiers and superiors who surround them. They kneel in the center of frame, each one with a bird in hand, and both focused intensely on the task before them. The twelve white men forming a circular boundary constitute the surveillance managers that these men must navigate. A presumptive jury of nonpeers, they are entertained and excited, perplexed, and bored. The ranges of facial and bodily gestures and clothing choices are meant to signal a visual hierarchy that race exacerbates. To the imagined question of what to do about the millions of black subjects on the cusp of freedom from enslavement, this photograph, like the one that precedes it, has an answer: excessive, demoralizing utility and the refusal of anything resembling inclusion. Out of this photographic conundrum we can see how the progression of violent engagements with black flesh evolved. Martin A. Berger writes, “For European-Americans, whiteness was not a stand-alone construct but one produced by a confluence of other dominant markers of identity. Objects were coded white to the extent that they exhibited (valued) traits associated with their essential nature.”16 Krista Thompson notes that photographs from the Caribbean in the nineteenth century presented black Jamaicans as “picturesque inhabitants who had been ‘civilized’ and disciplined by colonial rule.”17 Social stasis was thus photographically engineered. From there, it was not difficult to produce the imagistic scaffolding that facilitates photographic black death.

Mortevivum

Mortevivum is the term I have come up with to understand this particular photographic phenomenon: the hyperavailability of images in the media that traffic in tropes of impending black death. These tropes cohere around an ocular logic steeped in racial violence (and the nostalgia engendered therein), and they make any tragedy, any crisis, an opportunity for viewers to find pleasure in black peoples’ pain. The easy accessibility of a range of visual imagery adhering to these tenets constitutes the repetition of a way of looking measured by their staying power. Since photography’s invention, black life has been presented as fraught, short, agonizingly filled with violence, and indifferent to intervention. Living death in a series of still frames, refusing complex humanity.

Divided into three chapters, Mortevivum constructs the late modern advent of photography as uniquely positioned to make profligate the fungibility, to use Saidiya Hartman’s term, to continually frame the contours of black subjectivity. For the book, I examine four interlocking “locations” of visualizing slaughter: South Africa, Rwanda, Haiti, and the United States. Photography’s ability to render blackness as stagnation (via loss, crime, famine, poverty, and death) is visually normalized and held in place by the power of the imagery and our collective inability to see beyond the limitations of our cultural bifurcations. I am interested in how the viewer receives and processes images of the dying and the dead, particularly when those in the photographs are black. What I am calling a cartography of the ocular (moving from national location to national location, but always under the cover of blackness) has specific dimensions: a viable and recognizable enemy, the failure of other people’s sovereignty, and the global ability to reinforce white supremacist ideals.

Cartographies of the ocular manage to span the reach of antiblackness in the global world. They tell us how blackness is treated as a forfeiture of worth, offering evidence of this forfeiture in an avalanche of graphic imagery. An examination of Pulitzer Prize–winning photographs from the last forty years is instructive. Violent imagery coalesces around black subjects from present-day Zimbabwe to Ethiopia, to California, New Jersey, and Liberia. If we were to draw out a map illustrating instances of antiblackness, it would cover the known world. This book is the way I make sense of the depth and breadth of imagistic othering rendered black.

For mortevivum is, in its very construction, a photographic production. Although it has tendrils of other properties of representation, the term as I am deploying it is about the force and the power of photography in the field of production over which so much has been inferred and assumed. Documentary photography, to be precise, for it is within the space of the document that an adherence to what is constructed as evidence and realism in this genre takes center stage. Black subjects are perceived and remanded to the space of photographic stasis that consumes and corrupts their ability to be autonomous outside of the violence of antiblackness.

What could be more insistently destructive than the swift mobility of print imagery in daily newspapers, digitized and received in various forms of immediate consumption? This project explores photography’s import and utility on the cusp of the twenty-first century—at the tail end of analog photography, the beginning of the photographic digitization of imagery and the burgeoning prowess of the World Wide Web. This is a project that looks back to anticipate the forward thrust of a post–September 11 permissive objectification, as after 2001, the dead become a swirling mix of Middle Eastern and South Asian subjects, rendered as deserving of a photographic death and a permanently suspended life.18

The Body Enters the Archive

This is how you read a photographic image: I was greeted with marked illustrations of antiblack violence when, after living in Orlando, Florida, for five years, I returned to the city of my birth, New York. I arrived in early June 1994. Moving from one bus/train station to another, I had to readjust to the common presence of newsstands that dotted the city. I would linger as I had previously in front of these ubiquitous kiosks, surveying a range of daily newspaper front covers, deciding which would be worthy of my fifty cents. It took me months to work out why I was noticing something in repetitive patterns that I might have missed had I not spent some years away from the bustle of New York City. Each day as I maneuvered the streets in silence, I was met with jarring photographic renderings of black death. As I instinctively averted my eyes, I remember being unsettled, but I was unsure as to why. I knew enough about the “if it bleeds, it leads” mantra of late twentieth-century journalism, but here was something else. It was devoid of living “human images” and instead trafficked in specific dead bodies—corpses for which there was no need for regard. It was then that it hit me: all the dead bodies shown on the front page of multiple newspapers were black. It was as if there was an implicit agreement that black subjects were fungible in ways others were not. Furthermore, everyone looking at these photographs understood this too.

Indeed, antiblackness so organized the visual disposability of black subjects that the final decade of the twentieth century is filled with examples, large and small, of this repeated expendability found in documentary photography. Of the repetition of images of dead black bodies in daily newspapers during the 1990s, Deborah E. McDowell writes, “These post-mortems circulate specifically within a journalistic economy linked to the dissecting and quantifying obsessions of social science linked especially to its historically racialized obsessions with separating the ‘informative’ from the ‘deviant.’”19 Blackness intertwined with “objective” data acquisition is an engorged abscess of racialization always on the verge of rupture. When it finally bursts, it renders the wound of white supremacy healed (falsely), and always at the expense of black people. These images have very little to do with the purported evidence of news dissemination. Their informative offerings are always spurious and always open to critique. McDowell continues: “And even if they are seen, these post-mortems do not invite protest. Perhaps they do not strike readers as gruesome because the press has accustomed them to viewing the face of black death. Indeed, in contemporary public media and discourse, death is synonymous with blackness and constitutes the absolute limit of ‘difference.’”20 Blackness and death as “synonyms” is the tally here. How else to understand the century-long deployment of photographs against black humanity, the submersion of subjectivity alongside a rigid visual framework that constricts a fully embodied black presentation?

The Subject as Object

Photography has helped facilitate a subject/object fallacy wherein, under the guise of the evidentiary, black subjects are presented as objects of crises waiting for an external (white) articulation. Legibility here means being legible to viewers who traffic in the visual demise of those registering as black. The length and depth of this trafficking is a foreshadowing event that produces its own mechanism of engagement. To unpack and unfurl its significance, we must go back to move forward. If global antiblackness is the atmosphere, as Christina Sharpe reminds us, then photography clings invisibly to the skin like mist. This makes the ephemeral/stasis structure of mortevivum an unwieldy navigation.

Visual constituencies make the archive of unbelonging tenable and available. Where harm is done, they ask us to tread lightly while attending to all there is to see. Where value is assumed and expected, there is its constant reinforcement and a willingness to extend ocular grace. Where there is an understanding of collective disposability, dispossession is the navigation and the end point. The black subject’s quotidian existence is balanced between photographic dispossession and disregard, informed by a system that claims lives in the light and in the dark. So here we are, at a photographic demarcation point that now includes the continuing costs of white supremacy on black subjects globally.

Along with my reintroduction to newspaper imagery in the mid-1990s, there was a hovering poetic interlude—a space where it seemed black poets felt the need to engage the properties of the photograph that circumscribed black life. These articulations concern the force of photography and its historical longevity, an extension of life buttressed by the value placed on the genre’s purported claims. Lucille Clifton’s poem “the photograph: a lynching” is presented as a series of questions meant to expose the violence of lynching photography’s long history.

is it the cut glass

of their eyes

looking up toward

the new gnarled branch

of the black man

hanging from a tree?

is it the white milk pleated

collar of the woman

smiling toward the camera,

her fingers loose around

a christian cross drooping

against her breast?

is it all of us

captured by history into an

accurate album? will we be

required to view it together

under a gathering sky?21

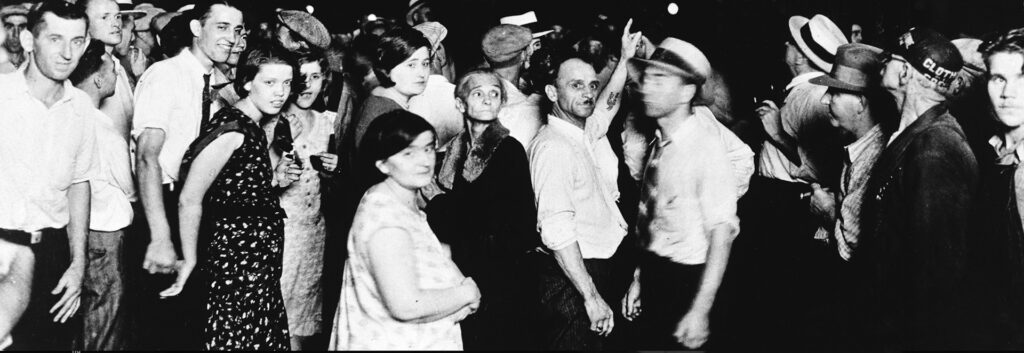

The long and horrific history of lynching photography in the United States is the origin point for a cruel framework set against black subjectivity. As Jacqueline Goldsby reminds us, it was the prurient spectacle offered by lynchings that held the white gaze with the promise of blackness aligned with death. Drawing on Roland Barthes’s exploration of the specificity of this thing that “has happened only once,” Goldsby writes: “Every lynching that ended in murder was its own ‘occasion’ of and ‘encounter’ with reality’s final limit—death.” And yet, for Goldsby, “once taken, moments captured by still-camera pictures do not exist in the historical present. For lynching to be represented in this medium, then, made the violence easier to disavow because photography transformed it into a spectacle that would prove impossible either to ignore or to see.”22 This crosshatching of regard and disregard creates a spectacle that mediates photography’s mundane violences and sets them on fire. The mechanism, photography, does not burn. It somehow evades that level of destruction in favor of the scars it leaves on some others, not all. This has more to do with cultural shifts in the imaginary that cleave to repetitive narratives.

I emphasize lynching imagery here for a number of reasons. The spectacular production of lynching photographs has a long, horrendous history. These photographs tell us something important about the communal ethos of white supremacist violence and the pleasure derived from its participants. As a terrorizing apparatus that brings pleasure and satisfaction to its participants, the anonymity among visibility is striking. These were not people hiding from photographers. They sought them out. They did not slink away from lynching scenes; they sent postcards, purchased at the lynching events, to friends and relatives across the country. Vicarious murder was the pursuit, and yet one would be hard-pressed to locate the attendees in the historical record. Mortevivum is the deployment of a contemporary application of vicarious murder. And much like a righteous viewer/participant at a public lynching, there are many ways to absolve oneself of the true gravity of the crime.

James Baldwin’s 1965 short story “Going to Meet the Man” offers us the parameters of the visual production of the lynching photograph without reproducing the visual image itself. Instead, Baldwin orders the before, during, and after of the event through the prism of white supremacist ideology embodied by the main character, Jesse. Past, present, and foreseeable future coalesce as Jesse negotiates the violence of his desire and the racism that precedes it. “Going to Meet the Man” layers racial hegemony over the physical proximity negotiated by each of the characters in the story. The narrative opens with a scene of stifled/failed intimacy in the space of the marital bed, as Jesse tries but fails to be aroused by his wife, Grace. His impotence hints at his sense of fragile masculinity. He is unable to be with Grace sexually or visualize his wife in this moment as he imagines that every black person he has ever known, abused, violated, or interacted with is there in the bed with them.

As his mind wanders, while Grace drifts off to sleep, his subconscious mind takes over as he recalls aloud the details of the beating given to a young black man at the sheriff’s office that day (he is a deputy sheriff). Baldwin writes, “As he talked, he began to hurt all over with that peculiar excitement which refused to be released.”23 At the center of Baldwin’s story is the national inheritance of violence and the spectacle of racial terror that functions like a series of moving images made into still frames. Saidiya Hartman writes in Scenes of Subjection: “Blacks were envisioned fundamentally as vehicles for white enjoyment, in all of its sundry and unspeakable expressions.”24 Between the marital bed, where Jesse and Grace fail to make love, and the memory of a road trip taken in the cavernous space of the family vehicle, the distance between public and private sites of intimacy are all comingled with black trauma, exploitation, and murder. In this way, Baldwin represents the domestic production of racial terror and patriarchy within its externalized public imagined community—that of the white voyeurs/participants of the mob lynching. Baldwin presents us with an interwoven tapestry of violence and desire that is passed from generation to generation.

In Baldwin’s ocular arrangement, lynching photographs embedded in the long arc of US history present the excessive and repetitive display of black visualized death, yet his story focuses instead on the interiority of those who traveled distances near and far to participate in these acts of mob violence and corporeal obliteration. Indeed, these people brought their children to these lynchings, and wore their best clothes. The story seeks to answer the questions, Who were these people? Where did they come from? And why were they so eager to document this violence photographically? Baldwin intimates that in viewing the gruesome murdered bodies of black lynching victims, we are looking at the wrong people.

Detail. Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, Marion, Indiana, August 7, 1930. Courtesy of Getty Images. This image has been altered from its original form.

“Going to Meet the Man” builds around a memory from Jesse’s past when his parents took him to witness his first lynching. As Jesse’s family journeys from home into an open field to watch the excruciating hanging and burning of an unnamed black man, we bear witness through Jesse’s eyes, fixed on his father (also named Jesse), and then his mother, among the crowd. Baldwin writes, “He watched his mother’s face. Her eyes were very bright, her mouth was open: she was more beautiful than he had ever seen her and more strange.” Jesse’s mother has dressed for the occasion, choosing a ribbon to place in her hair as an adornment. It is essential that she offer the crowd, as well as the soon-to-be lynched man, a vision of white womanhood worth dying for, worth killing for.25 As the eyes (Jesse’s) watch the eyes (his mother’s) that are eagerly absorbing the sight of the lynching, desire is formed. “He wanted death to come quickly,” Baldwin writes of Jesse while he is submerged within the mob. However, “they wanted to make death wait.”26

Sandy Alexandre considers the place of landscape in the context of public lynching scenes. She writes of lynching trees: “Their branches and their height: perfect for human display. Their status as natural objects: conveniently implicated in white society’s efforts to naturalize what is (in effect) a social crime. Their being symbols of life: ironizing, in plain view, the gruesome scenes of death that take place on their watch.”27 Baldwin claims the landscape as just one more instrument of terror for black subjects. He makes clear that inside or out, in the presumed safety of home or the industry of work, there is no place that white supremacy will leave without terror.

The arc of Baldwin’s imaginative trajectory is something akin to the photographic entanglements of race, class, gender, nation, and space. In “Going to Meet the Man,” the subtle interplay of staging and seeing reveals an American self-portrait: a violently constructed articulation of white supremacy that presents itself as order, beauty, and virility, a repeating lie that finds the true image of itself in the repetition of that lie. Jesse remembers: “He could not see over the backs of the people in front of him. The sounds of laughing and cursing and wrath—and something else—rolled in waves from the front of the mob to the back. Those in front expressed their delight at what they saw, and this delight rolled backward, wave upon wave, across the clearing, more acrid than the smoke. His father reached down suddenly and sat Jesse on his shoulders.”28 In assuming the viewer’s familiarity with lynching photographs, Baldwin is suturing racial violence to the vagaries of leisure and spectacle, the “delight” disallowing the force of white anonymity to dominate what we already know about crowds like the one in the story. Here the lynched man’s body serves as an afterimage of the violent photographs that will haunt the southern landscape, then disappear into the temporal archive of history. Baldwin’s photographic production, the ebb and the flow of his gestural, expressive, contemplative visual display, is part of his decades-long engagement with the world of the visual.

After the lynching, Jesse and his family walk away, into the attendant violence of their whiteness and the safety it affords them. Meanwhile, “the black body was on the ground, the chain which had held it was being rolled up by one of his father’s friends. Whatever the fire had left undone, the hands and the knives and the stones of the people had accomplished. The head was caved in, one eye was torn out, one ear was hanging. But one had to look carefully to realize this, for it was, now, merely, a black charred object on the black, charred ground.”29 To encounter Baldwin’s prose is to delve beneath the depths of human frailty and foreclosure, knowing how violently imagistic is what is buried there. It is to consider the primacy of the visual as it orients the lives and labors of the citizens it refuses or holds close. To think of Baldwin, then, as one of the country’s foremost theorists of race and the visual is to place him within the canon of interlocutors without whom we would have no contemporary discourse of contemporary visuality. His powers of observation were the enduring result of measured, potent analysis, cultivated over the course of many years, through several literary genres and in photographic presentations.

According to Mark Sealy, “Colonial and racist trophy photographs therefore serve as fragments and frames from within the grand narrative of white supremacist visual ideologies. They allow us to enter the catastrophic frames of violent colonial and racist times, and they become important articulations that signify the dark cultural codes constructed against people of African descent or others classified as inferior.”30 These “important articulations” are a hierarchical road well-traveled and rarely mentioned. Photographs serve as guideposts along this road, able to emulate interest as benign even as the violence of ocular practices is ever-present. Under the ruse of “evidence,” blackness survives through the destructive properties of the visual. Misrecognition meets indifference in a surfeit of imagery meant to foreclose the autonomy, will, and humanity of the subject. To be encased in this imagery, held beneath its twisted apparatus of the gaze, is to enter a carnival house of mirrors where the black subject is the only object of engagement. “The circus and the audience,” Baldwin writes in The Evidence of Things Not Seen, “are absolutely indispensible to the hygiene of the state.”31 The spectacle is the point. Without it, Baldwin suggests, internal chaos will produce the kind of havoc that a deputy sheriff will find impossible to control.

The hypersurveillance black people experience at the hands of the state or as part of some consumerist ethos makes the double consciousness that W. E. B. Du Bois discussed in the early part of the twentieth century photographic in its extension. “The historical formation of surveillance is not outside of the historical formation of slavery,” Simone Browne reminds us.32 Nor is it outside the history of imperial possession. It is, as is now understood, an interlacing of possession and disregard, the permissive inculcation of ocular violence. Someone must be available for this ocular violence, for it has to exist and extend itself forward. Black diasporic subjects are the canvas upon which so much is thrown: racial, national, juridical, and cultural detritus get tossed onto them like projections on a film screen. However, this film has no locatable producer. It runs without a discernible source of power.

Antiblackness so measures the power of looking, seeing, and unseeing that Ralph Ellison structured his novel Invisible Man around this peculiar relationship between seeing and invisibility. Toni Morrison perfected the violence/indifference matrix in her novel The Bluest Eye. When protagonist Pecola Breedlove hands her money to the white immigrant shopkeeper, the exchange is instructive: “At some fixed point in time and space he senses that he need not waste the effort of a glance,” Morrison writes. “He does not see her, because for him there was nothing to see.”33 Antiblackness informs the line of sight and reveals a repetition of responses that suggest viewers “need not waste the effort of a glance”; black people go about their lives with the knowledge of this corporeal vulnerability for which no one, other than themselves, is responsible. Thus, with none of the protections of the state, but with all of its violent inflictions, photography offers one more option to view black people in pain for the viewer’s enjoyment.

Some may challenge the idea that there is pleasure in this endeavor; however, one way to refute this is to see how agitated people get when you ask them to stop. Over a dozen years of conversations and presentations, the most consistent question I have received is about the evidentiary. In essence, I am asked about the essential nature of photographic evidence. “Don’t we need these photographs to know what is happening?” I am asked. To which my current response is, “What is the evidence we have that white people die?” The response to this question often results in awkward silence. It is precisely this understanding that white supremacy provides but disavows. White lives are valuable—too valuable to be reduced to photographic objects. They will not be visualized as dead bodies strewn across the front pages of newspapers. They will not be displayed anonymously as symbols of crisis and disorder. Their suffering will not be fodder for the failures of the state. It’s the privilege of an invisibly operating sempervivum where the perception is that dignified representation is the domain of white subjects, who are precious and therefore deserving of life. This is how the violent pushback against a phrase like black lives matter is so energized.

What is embedded in an insistence that the particularities of blackness justify documentation of the infliction of violence that would be appalling to consider for others? Here, that the “all” is not just unrealizable but pointedly antiblack, for other racialized subjects can be sustained within “all,” but only black is black. Photography gives the illusion of realism, allowing viewers to cement black progress with the visual residue of regression. This ensures that black lives are encapsulated within a two-dimensional space of cultural decline as if it is impossible to imagine what is beyond the photographic frame.

Mortevivum highlights the space between the materiality of the photograph (the living thing) and the visualization of antiblackness (the dead offering). It is here that imminent death is engineered within and beyond the photograph as a projected death drive forced upon black subjects so that others may understand themselves through other peoples’ bodies. The black diaspora exists for these viewers as a kind of cudgel against actual death, for in this sense the gravity of death is presented as a quotidian act of nothingness for the darker races. Aime Cesaire writes: “I make no secret of my opinion that at the present time the barbarism of Western Europe has reached an incredibly high level being only surpassed—for surpassed, it is true—by the barbarism of the United States.” We know that the “barbarism of the United States”34 is a nearly boundless series of violations against humanity that the country has yet to acknowledge and reconcile. We also know how racial stratification has buttressed and extended the line of sight for these violations and how easily the country has navigated both its innocence and its defense.35

Photography’s global emergence in the nineteenth century grafted onto the eugenics movement and imperial dispossession writ large. It is how the mandates of capture and progress severely restricted the line of sight for black subjects who had to use the same frame that was intended to contain them. “The camera relieves us of the burden of memory,” John Berger laments. “It surveys us like God, and it surveys for us. Yet no other God has been so cynical, for the camera records in order to forget.”36 It is the violence within forgetting that emphasizes black stasis on photographic film. This book endeavors to undermine the harm inherent in a refusal to acknowledge harm. When photography is aligned with blackness, it is suffused with a “serious pathology” that Morrison reminds us is always hovering in the shadows. And because it is hovering, this makes every interaction with the archive fraught with the pursuit of discernible destruction. As Stuart Hall has theorized, “The ideological construction of black people as a ‘problem population’ and the police practice of containment in the black communities mutually reinforce and suppress one another. Nevertheless, ideology is a practice. It has its own specific way of working.”37 In other words, ideology works visually.

Chapter 1 of Mortevivum, “The Empire,” explores the struggle with unbelonging that black South Africans share with African Americans in the historical order of racial segregation. Since the election of the National Party in 1948, South Africa has functioned within the racial and juridical rule of a white minority and the resistance of and to a black majority. Photographs manage the daily acts of removal, capture, violence, and denial perpetrated against black South Africans. “For years, apartheid politicians—and these, one should not forget, include apartheid’s last president—did not regard the liberation aspirations of blacks with any seriousness,” writes Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela.38 And images in the national media bear this out.

This chapter brings together empires within nations and their relationship to racial subjugation. South Africa and the United States are intertwined in a loop of racial violence meant to remind black subjects of their lower-class status mandated via the state. For South Africa, this is done via the apartheid regime, while the United States has a longer history of de facto and de jure racial classification. It begins during slavery and continues after slavery is abolished with the end of the Civil War in 1865. Apartheid ends officially, with the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994, but the reverberations of the regime are still currently in effect. Images reinforce the way apartheid rendered its black subjects outside citizenship and outside regard. Similarly, Jim Crow segregation in the United States and its attendant imagery extended the visualization of dehumanization from the nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth. From the end of the Civil War through the hideous decades of the American reconstruction era and beyond, white supremacy revealed itself via presentations of dead black bodies that are striking in their ubiquity, revealing a long history of visualizing the violent deaths of African Americans.

Chapter 2, “The Viewer,” concerns the proliferation of death that Rwanda represents during the 1994 genocide, which exists devoid of the photographs that would correspond to the slaughter of one million people in one hundred days. Instead, news media outlets mostly minimized or ignored the violence taking place in the small, central east African nation, preferring, apparently, to allow the war to reach its organic end without intervention. The gruesome images of dead bodies in various stages of decay do emerge. They emerge in the aftermath of the genocide, when most of the victims of the genocide are beyond any humanitarian intervention. These images, then, are not released at the behest of the victims’ families, or to highlight the determination of the perpetrators of violence. They are meant to remind viewers that blackness comes with a corresponding violence that no human intervention can abate.

This chapter interrogates the desire on the part of the viewer to participate in a proximity to death, using black people’s bodies with the understanding that this vicarious exchange allows the viewer to see everything and nothing at all in the endeavor. Antiblackness disallows points of reflection and consideration of the dead, as Rwanda occupies an unwieldy place in the documented presentation of a nation in crisis. This is where all previous mandates about photographing the dead and dying are violently, relentlessly deepened. And a deafening silence during the war and genocide translates to a visual cacophony afterward, when victims’ and survivors’ pleas have been ignored.

Chapter 3 of Mortevivum, “The Sentiment,” concerns Haiti in the public imaginary. The first black republic in the Western hemisphere is also the first nation to violently abolish slavery and create a nation out of its ashes. I argue that Haiti’s success as a former colony of France is continually undermined by photographic “evidence” of its sovereign failure. Images try to reinforce the idea that the formerly enslaved cannot overthrow their masters and survive to tell the tale.

When the US military was deployed to Haiti in September 1994, it was to facilitate what was called Operation Uphold Democracy, an effort to overturn the military coup that removed the democratically elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Lasting only a few months, the intervention was documented with hundreds of photographs in daily newspapers and weekly magazines, all seemingly intent on offering the nation up as devoid of leadership, autonomy, and agency. Indeed, the vast majority of images of the dead discussed in this book are from Haiti, where the US military was perpetually present, and so were photojournalists whose documented images reinforce the narrative of Haiti’s failed sovereignty.

Mortevivum takes a purposeful textual movement from south to north and back again to illustrate the circumnavigation of antiblackness where it occurs over time. As such, I am moving through several temporal locations in order to grapple with the global nature of antiblackness that pervades photographic archives of the present and past and impedes gestures of resistance for the future. The photograph as a living thing, antiblackness as a dead offering: We live in a repetition of imagery signaling who lives and who dies on a gelatin silver print. On a page in a book. On the cover of a newspaper. And in the memory of millions.

Note 1

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 79.

Note 2

Michael S. Harper, Images of Kin: New and Selected Poems (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1977), 132.

Note 3

In the “disciplining” sphere of photography, black subjects have had to contend with bifurcated representation: one part interest and one part exploitation. The latter emphasis has dominated a global field of vision that continues to shape the order of investment from healthcare to law, social engagements, and everything in between.

Note 4

John Tagg, The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

Note 6

In Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” Section 51, the speaker declares, “Do I contradict myself? / very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes).” Whitman, “Song of Myself,” in Leaves of Grass (New York: Simon & Schuster, [1855] 2006).

Note 7

Social progressives in the late nineteenth century in the United States were fixated on photography’s potential to aid in the documentation of the ills that society seemed determined to produce. “The 1890s had begun with American society in the grip of a long crisis,” Alan Trachtenberg writes. “For a dozen years the economy had fallen, creating hardship, especially for farmers and workers. Labor conflicts had grown sharp and frequently violent, as industrial workers increasingly resorted to the strike to defend their interests and win recognition of their unions. As conditions worsened, cities became a major focus of attention.” Overlapping with the Great Black Migration from the rural south to cities and to the north, African Americans make up a good number of the human subjects traced during this time in American history. Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History: Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill & Wang, 1990), 170.

Note 8

Alexander Gardner, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (New York: Dover Publications, 1959).

Note 9

Anthony W. Lee and Elizabeth Young examine Gardner’s Sketch Book for all its symbolic representations of the racial status quo. Lee writes, “Black men and women visibly appear in only six of its one hundred images, and only in their most caricatured antebellum roles—as meek servants, childish entertainers, or brute laborers for their white folk.” Lee and Young, On Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 47.

Note 10

Michèle Pearson Clarke, “A Dark Horse in Low Light: Black Visuality and the Aesthetics of Analogue Photography,” lecture, Gallery 44, Toronto, ON, November 9, 2017.

Note 12

Beaumont Newhall, “The Mirror with a Memory,” in The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1964), 17.

Note 13

Deborah Willis, A Small Nation of People: W. E. B. Du Bois and African American Portraits of Progress (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2003), 51.

Note 14

Bongani Madondo, “Making Memories: Reshooting Postcards from the Edge of South Africa’s Pop Culture History,” Daily Maverick, July 10, 2021.

Note 15

Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 60.

Note 16

Martin A. Berger, Sight Unseen: Whiteness and American Visual Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 57.

Note 17

Krista A. Thompson, An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 78.

Note 18

Media images traffic in the visual repetition of a Muslim other, one who can be folded neatly into an articulation of terrorism that is legible to a mass audience. For more on media representation and Muslim identity, see Evelyn Asultany, Arabs and Muslims in the Media: Race and Representation after 9/11 (New York: NYU Press, 2012).

Note 19

Deborah E. McDowell, “Viewing the Remains,” in The Familial Gaze, ed. Marianne Hirsch (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1999), 155.

Note 21

Lucille Clifton, “the photograph: a lynching,” in Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems 1988–2000 (New York: BOA Editions, Ltd., 2000), 19.

Note 22

Jacqueline Goldsby, A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 229.

Note 24

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 23.

Note 25

In Gwendolyn Brooks’s famous poem about Emmett Till’s lynching at the hands of white supremacists in Money, Mississippi in 1955, she presents the wife of one of the murderers, Carolyn Bryant, as immersed in the gendered application of racial patriarchy. “It was necessary,” Brooks writes of the white woman whose complaint about fourteen-year old Till set the lynching in motion, “To be more beautiful than ever. / The beautiful wife. / For sometimes she fancied he looked at her as though / Measuring her. As if he considered, Had she been worth it? / Had she been worth the blood, the cramped cries, the little stuttering bravado, / The gradual dulling of those Negro eyes, . . . He must never conclude / That she had not been worth It.” Brooks, “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon,” in Blacks (Chicago: Third World Press, 2000), 335–336.

Note 27

Sandy Alexandre, The Properties of Violence: Claims to Ownership in Representations of Lynching (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2012), 45.

Note 30

Mark Sealy, Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2019), 113–114.

Note 32

Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 50.

Note 34

Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 47.

Note 35

In White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), Gloria Wekker examines the structure of racial stratification in a Dutch context that willfully refuses to acknowledge its own racism and xenophobia.

Note 37

Stuart Hall, Selected Writings on Race and Difference, ed. Paul Gilroy and Ruth Wilson Gilmore (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 102.

Note 38

Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, A Human Being Died that Night: A South African Woman Confronts the Legacy of Apartheid (New York: Mariner Books, 2003), 61.